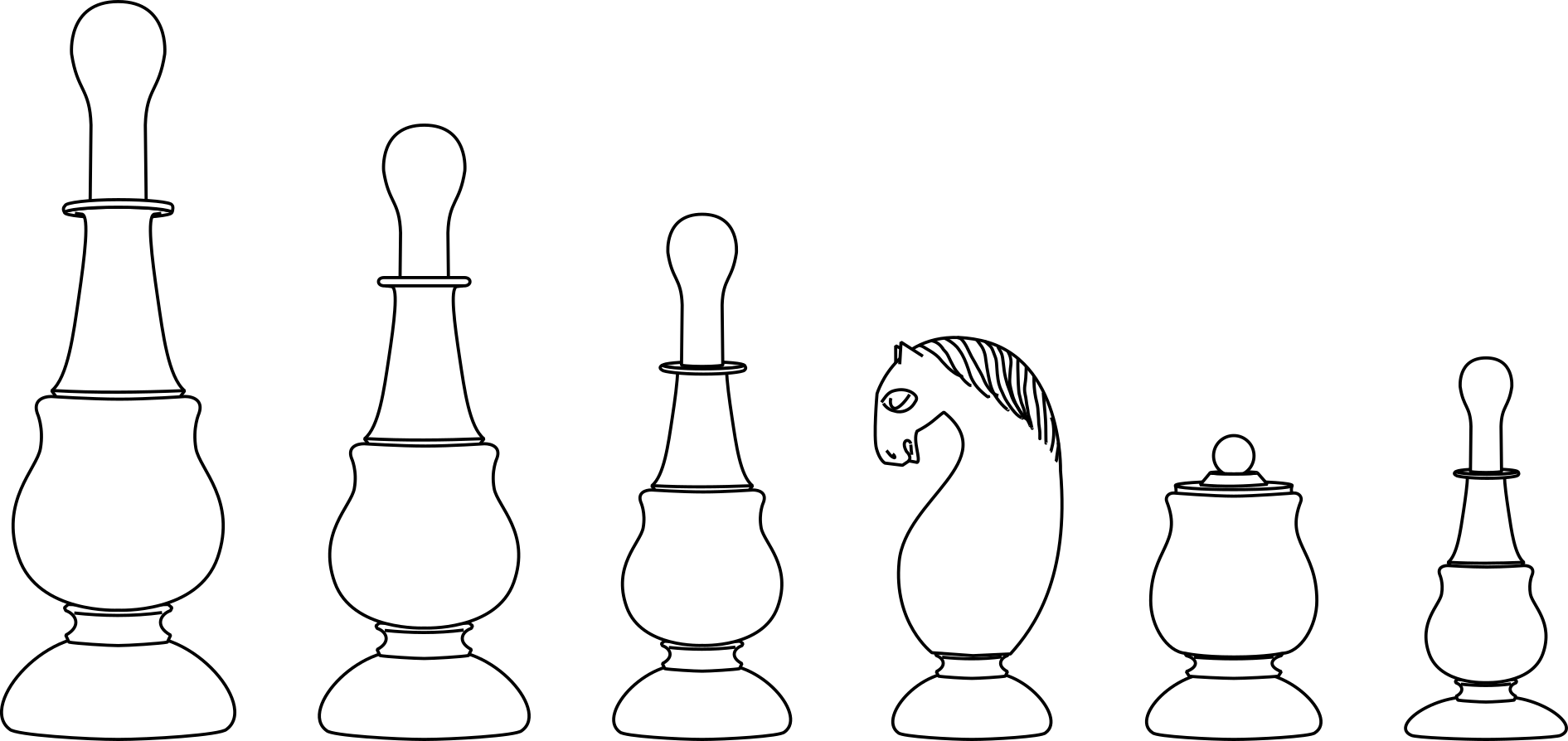

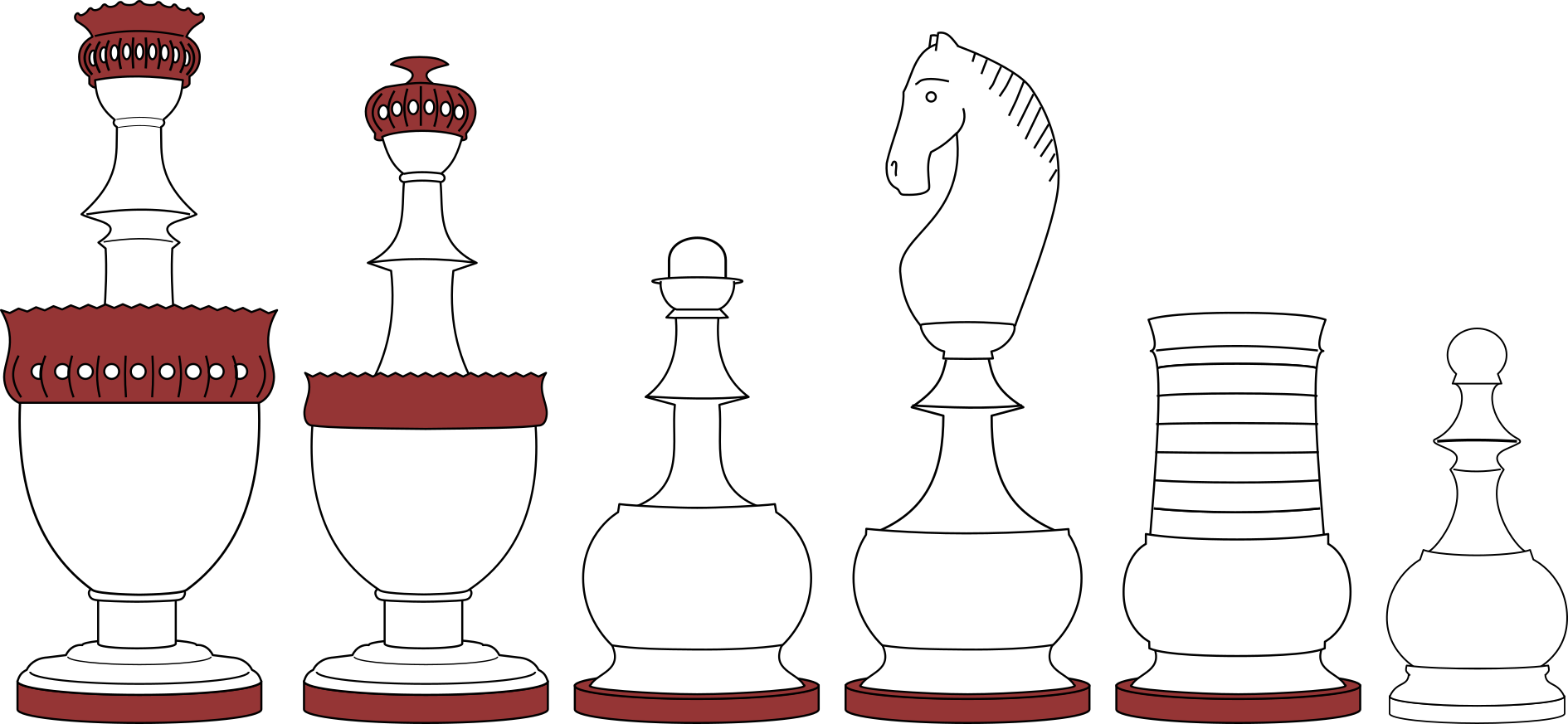

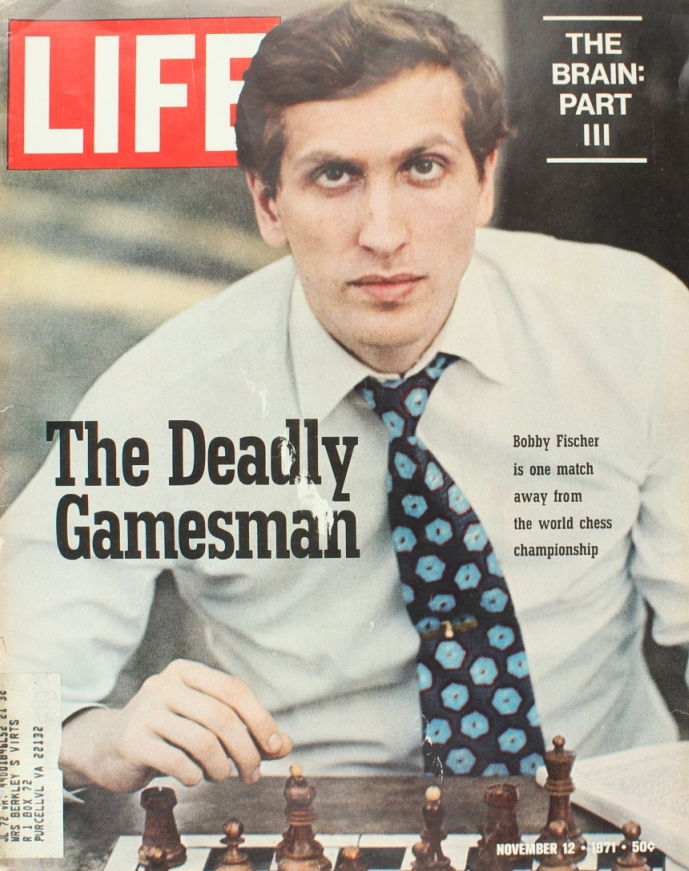

1950 (but see text)

"Turkish"

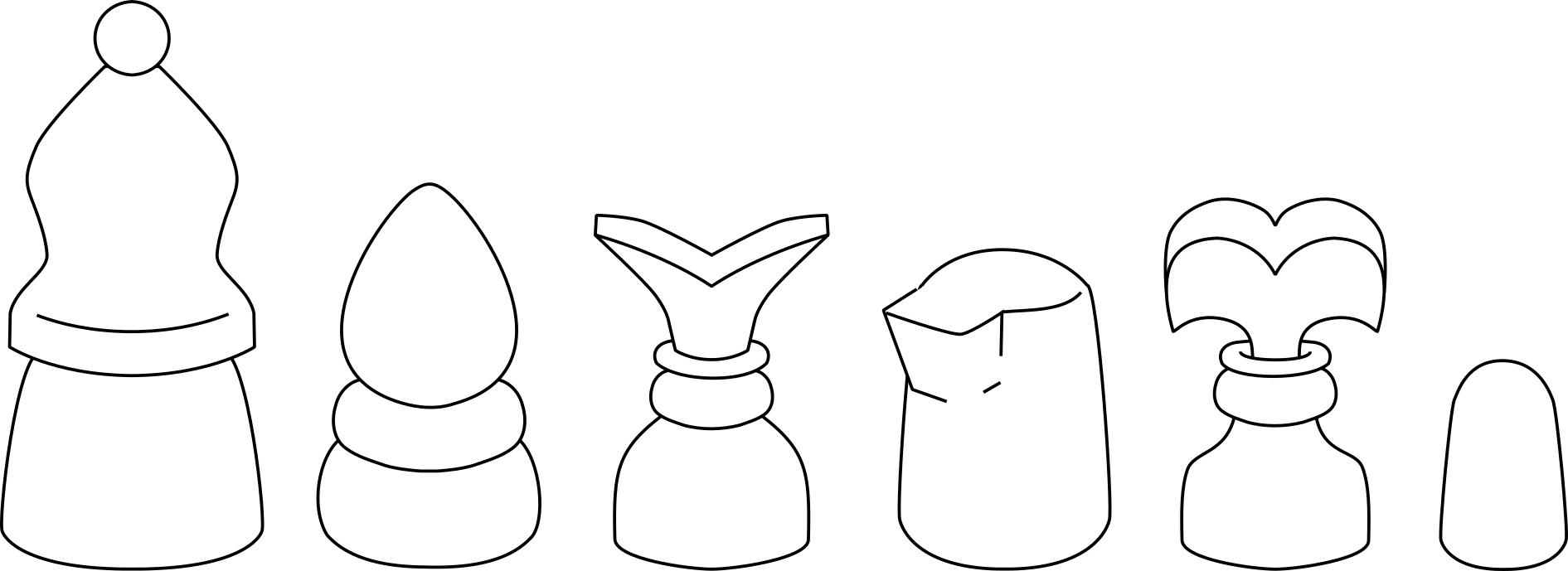

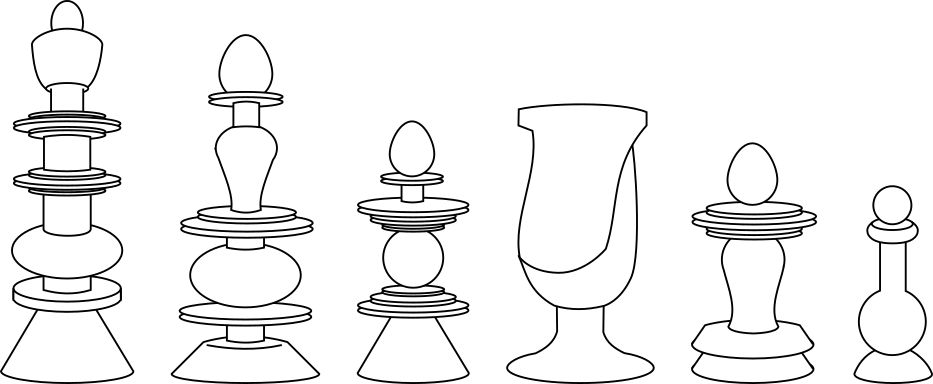

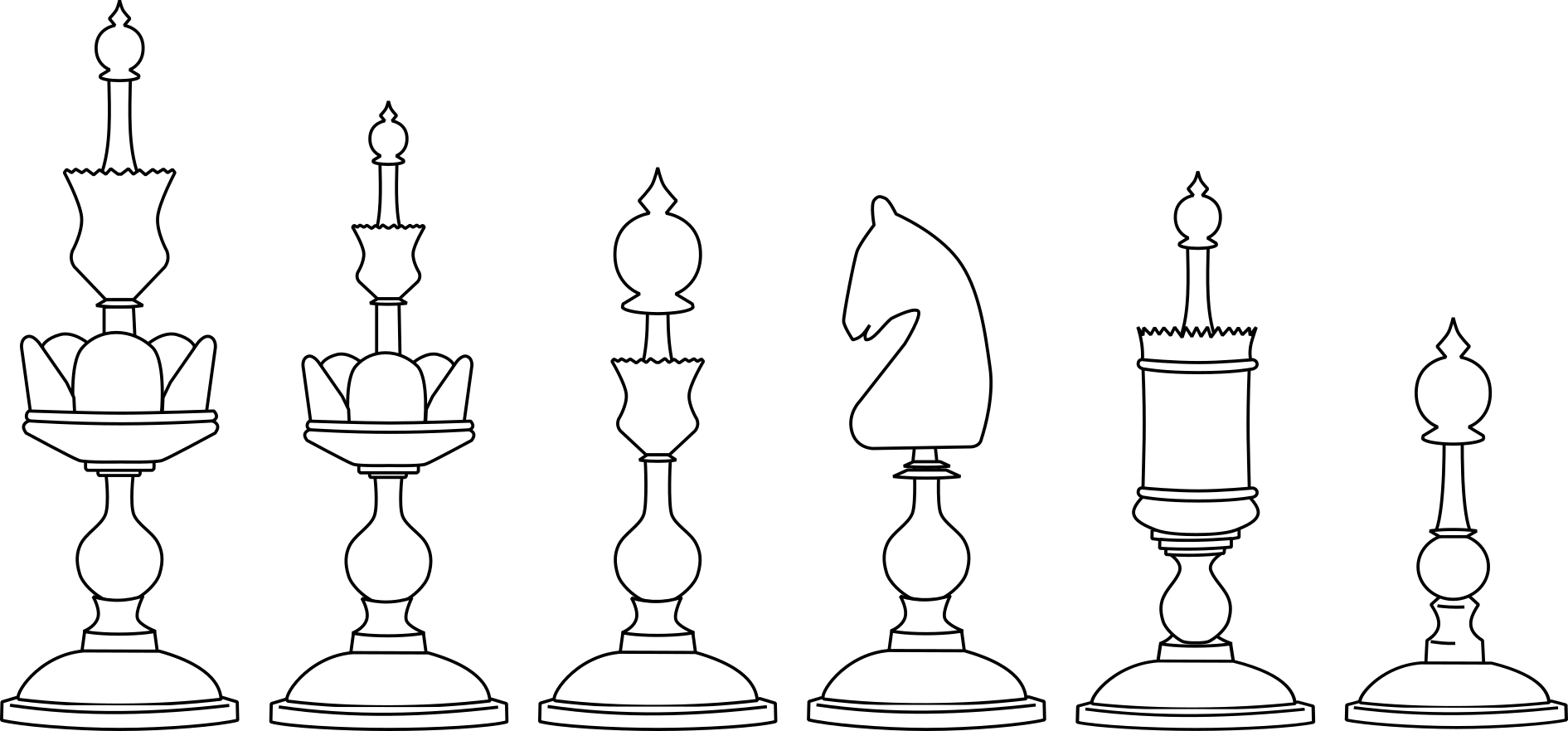

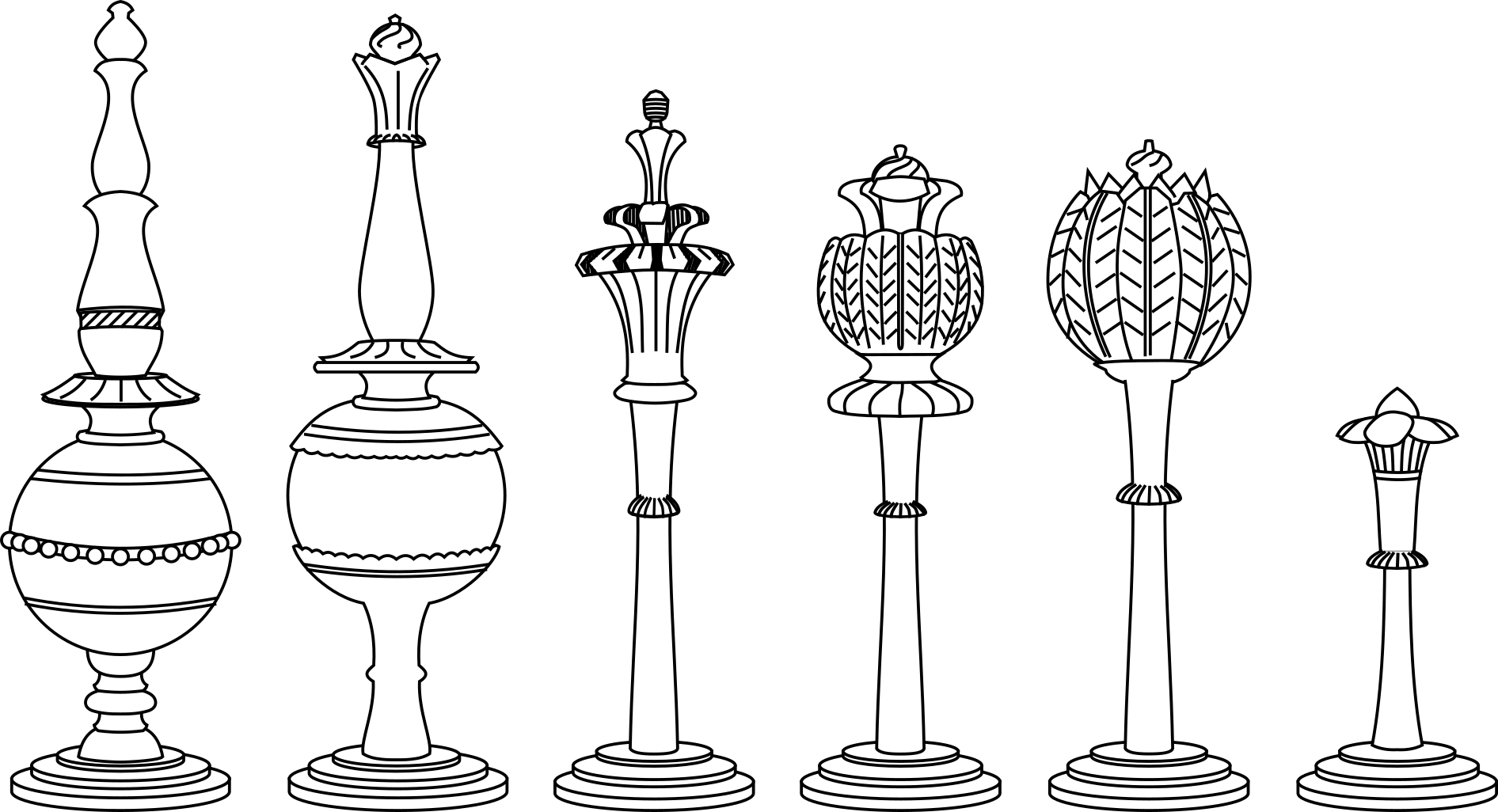

The placing and description of this pattern has caused me some difficulty, not least because of the paucity of examples. It has been asserted that these have a Turkish origin and some sets have been sold as 19th Century. At least some of these sets were made in Britain in the 1950s. Whether they really were based on earlier examples from Türkiye or elsewhere is speculative.

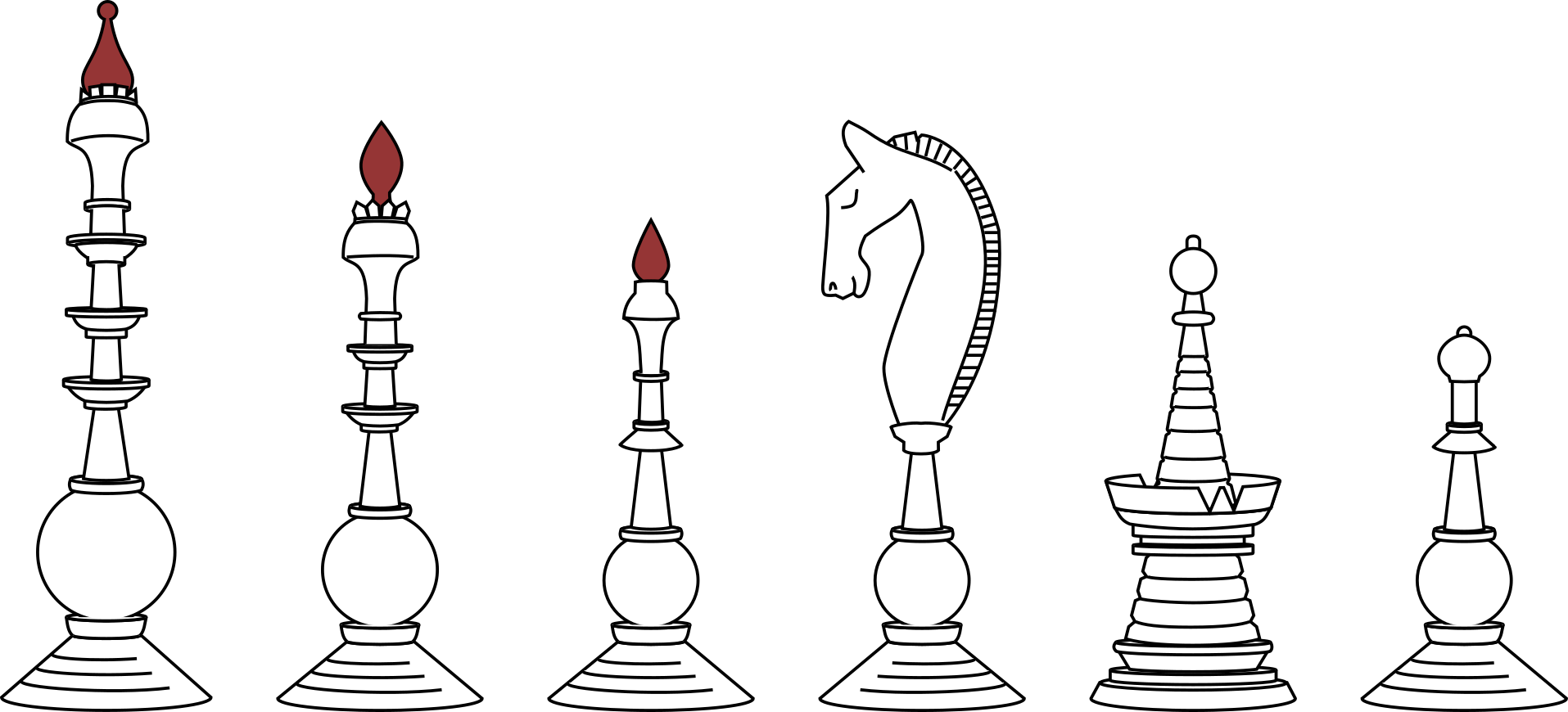

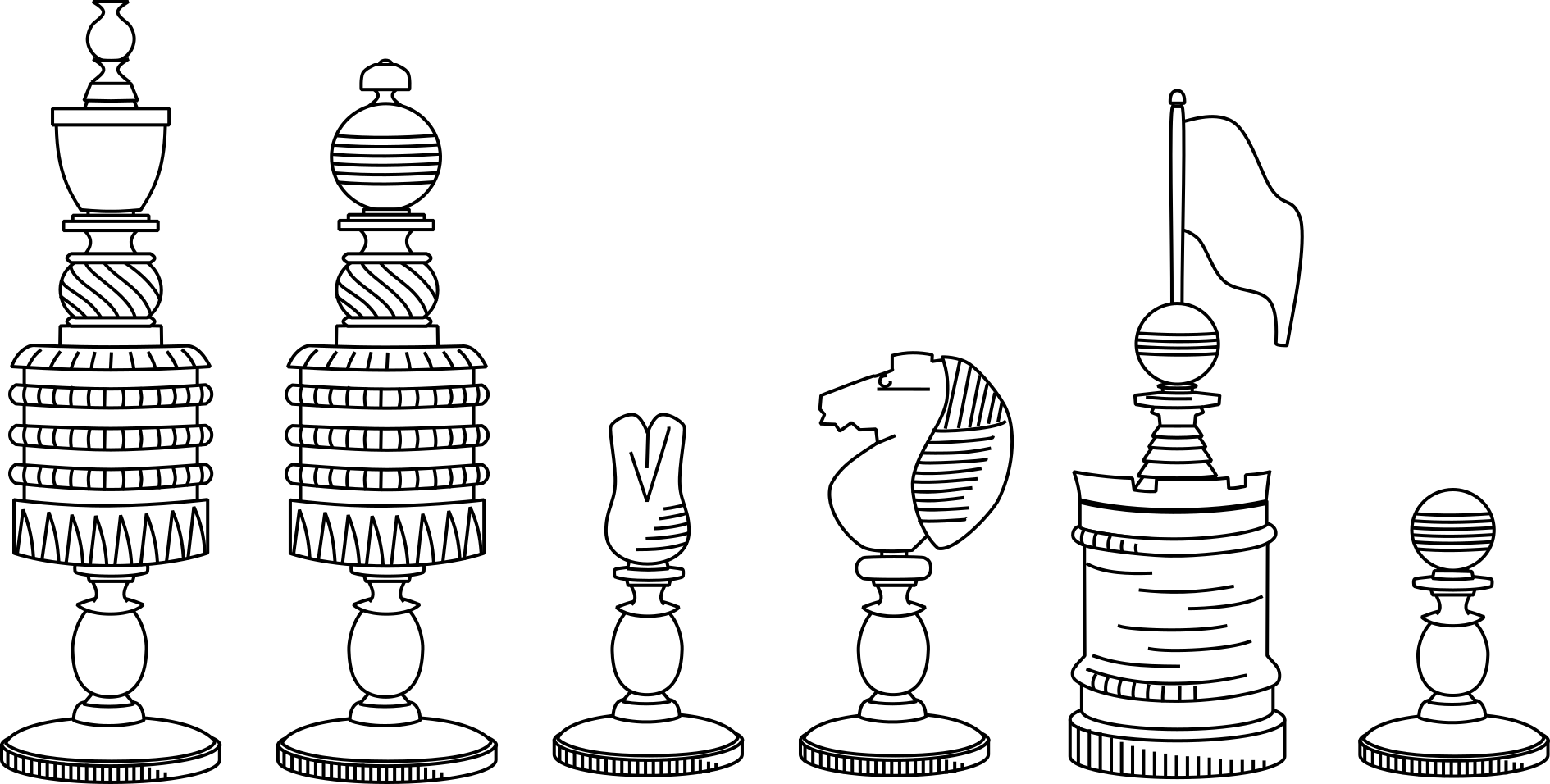

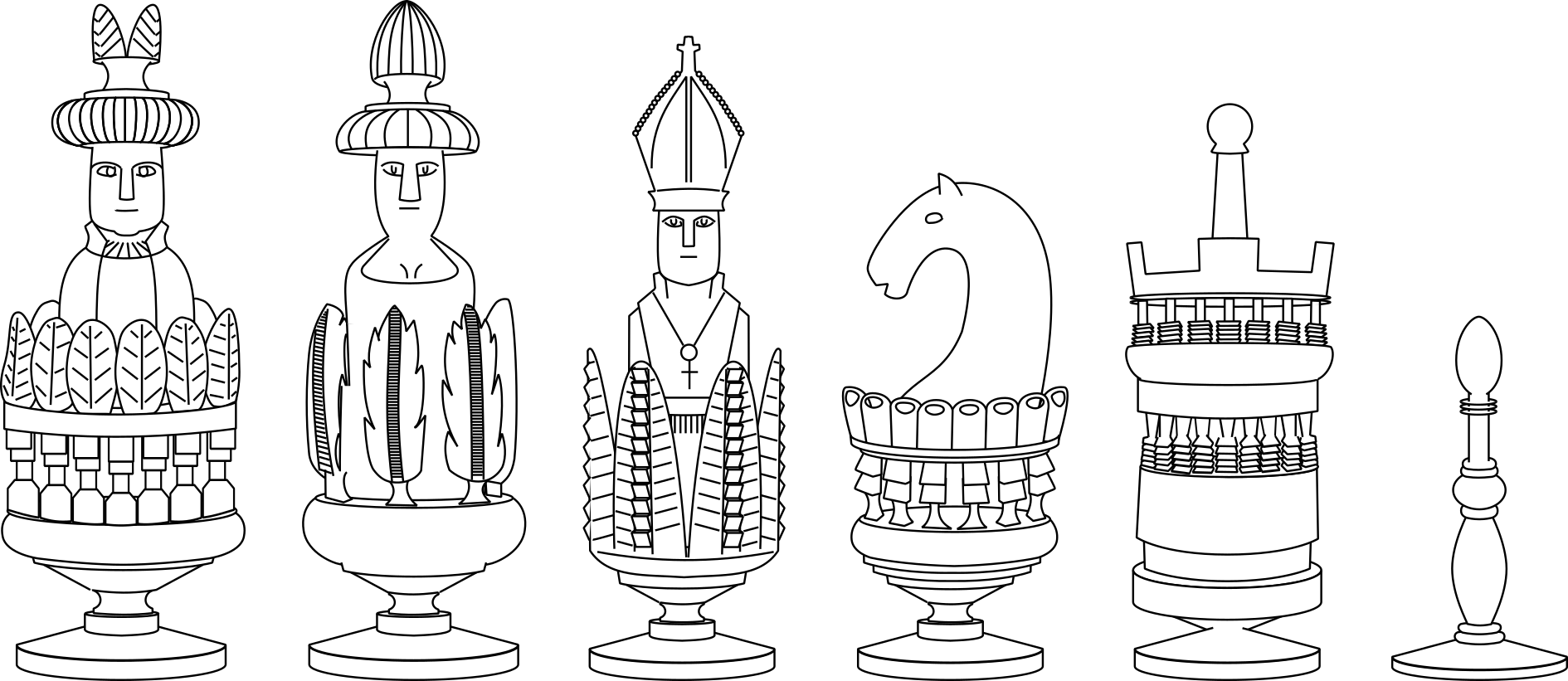

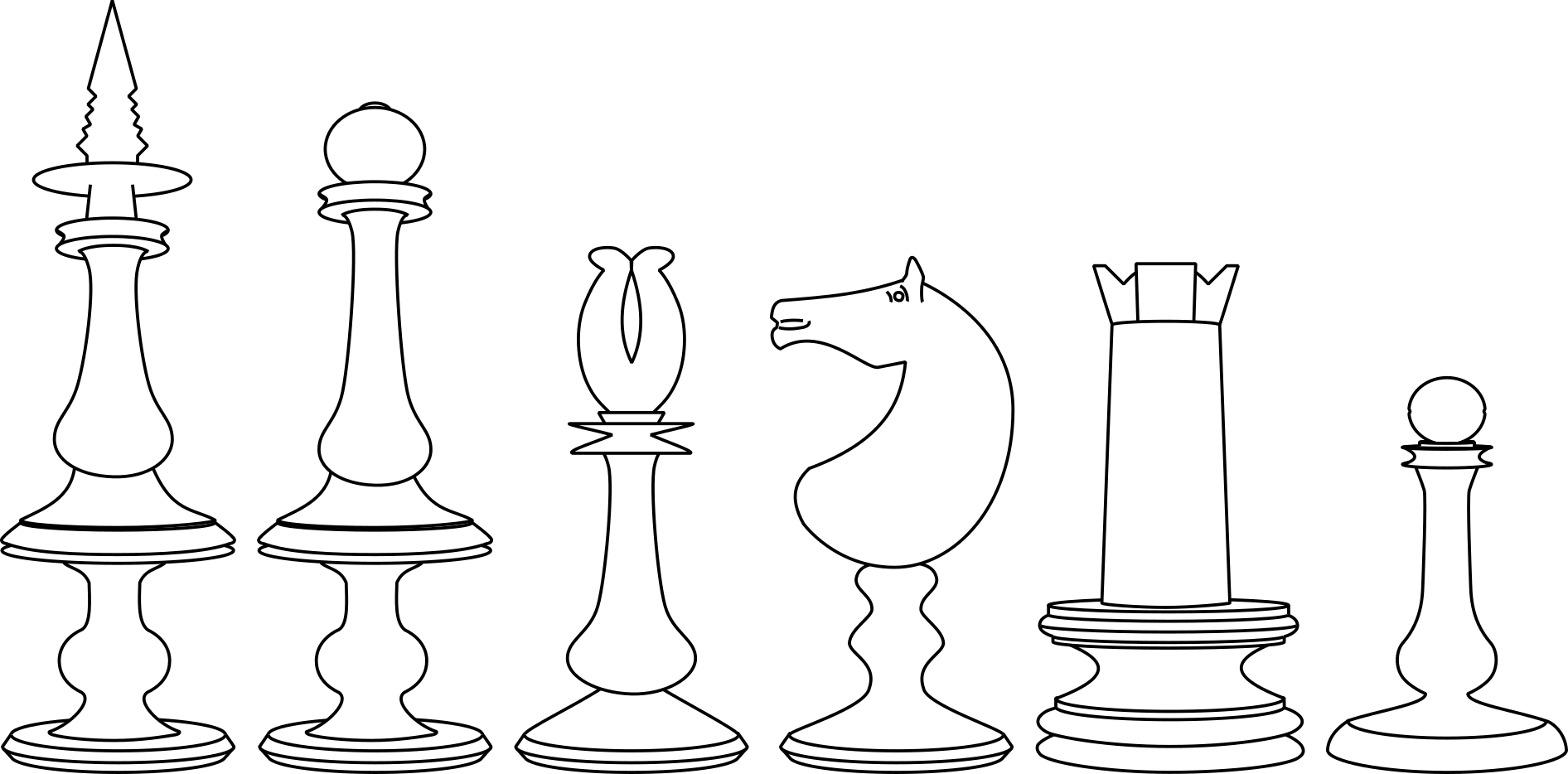

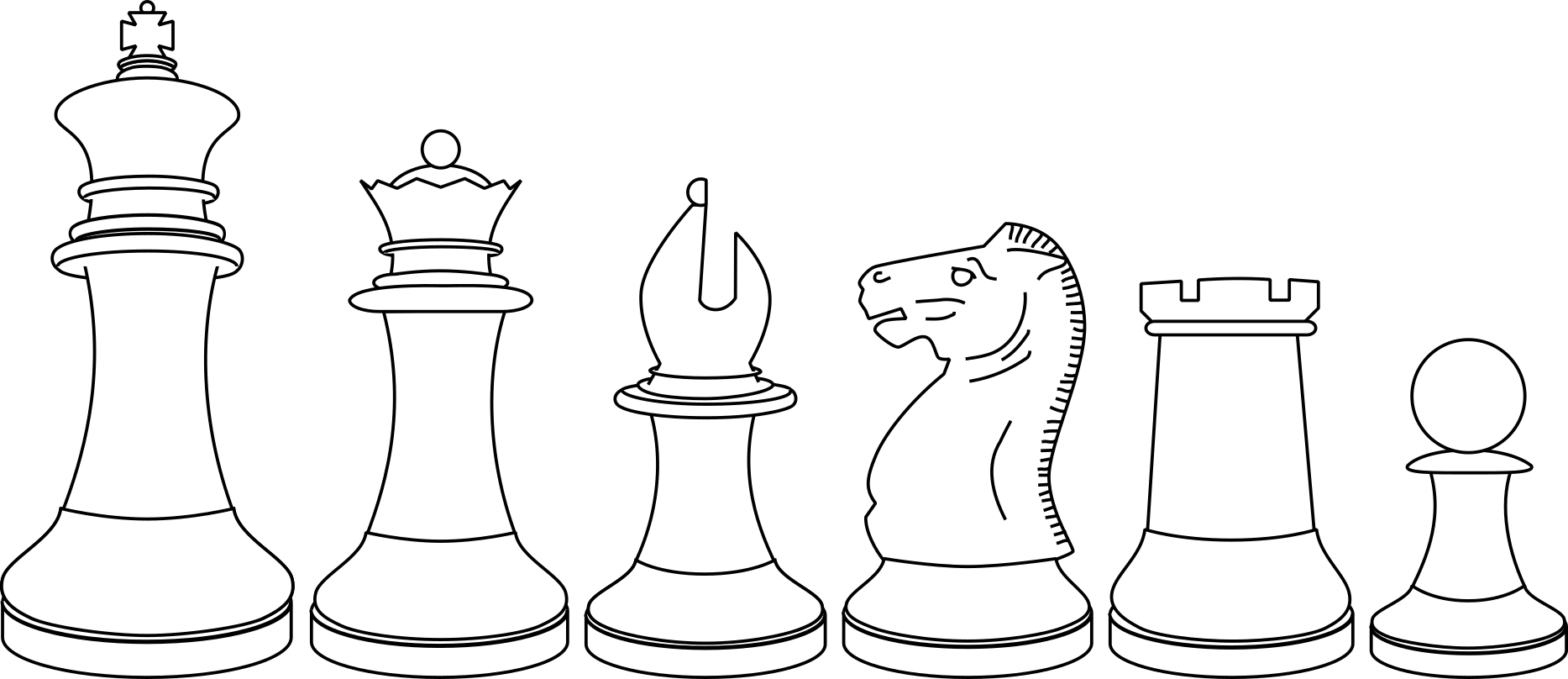

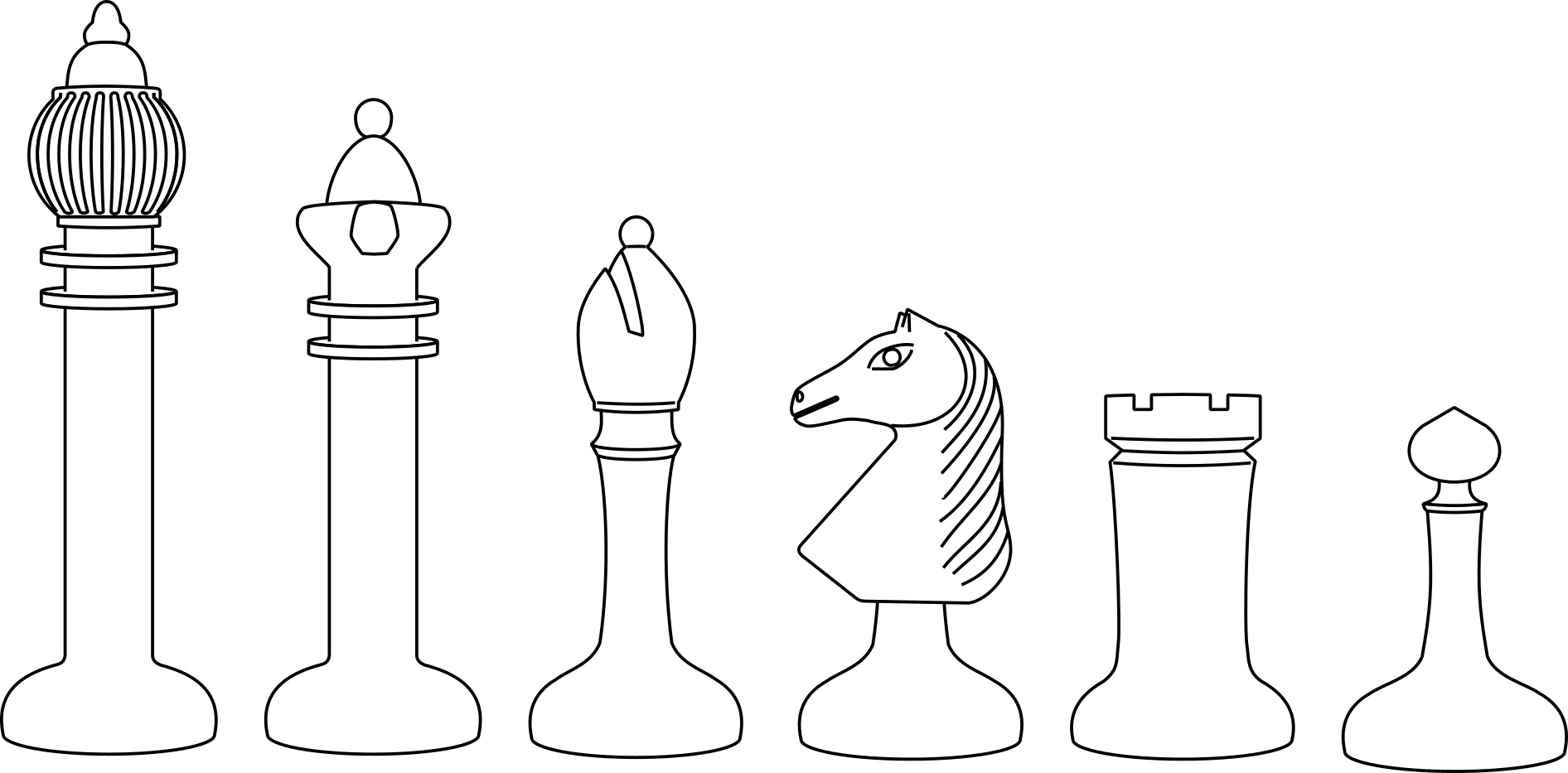

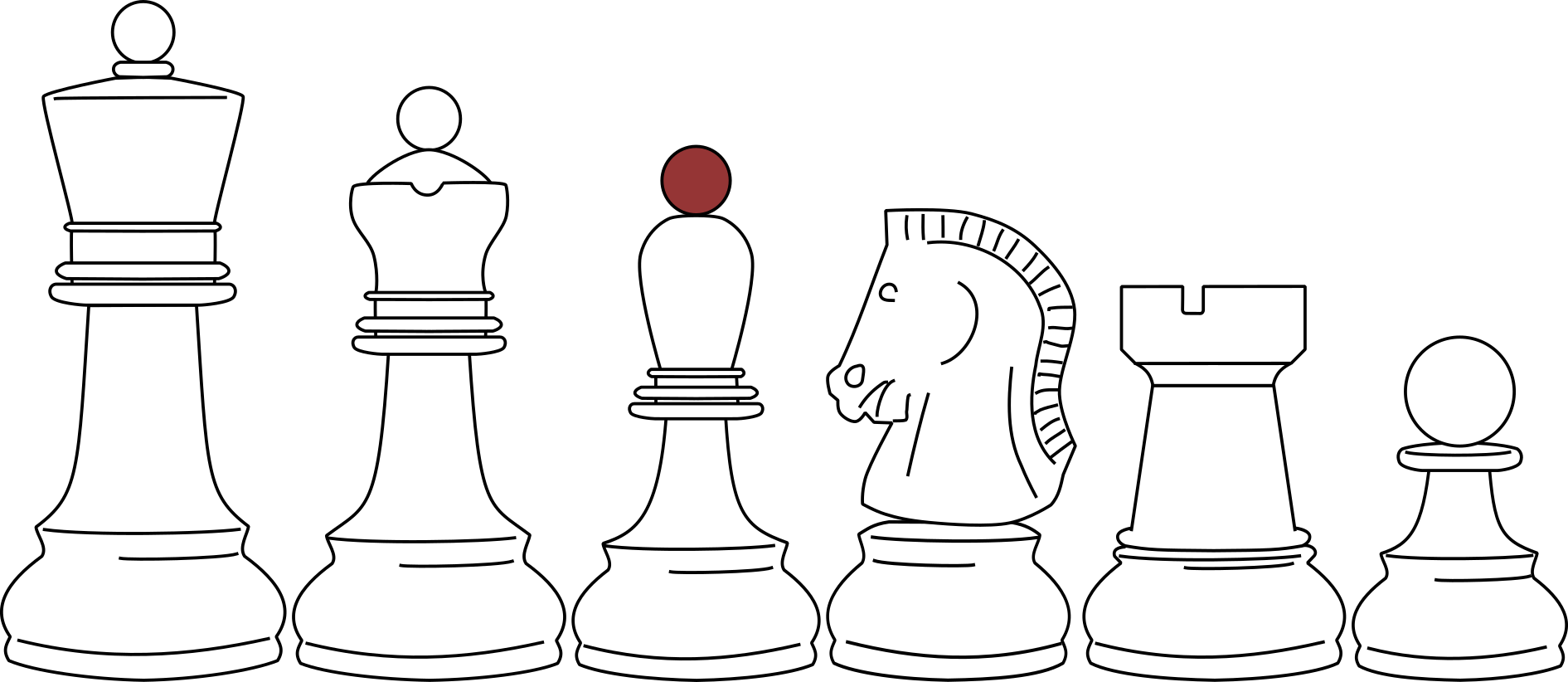

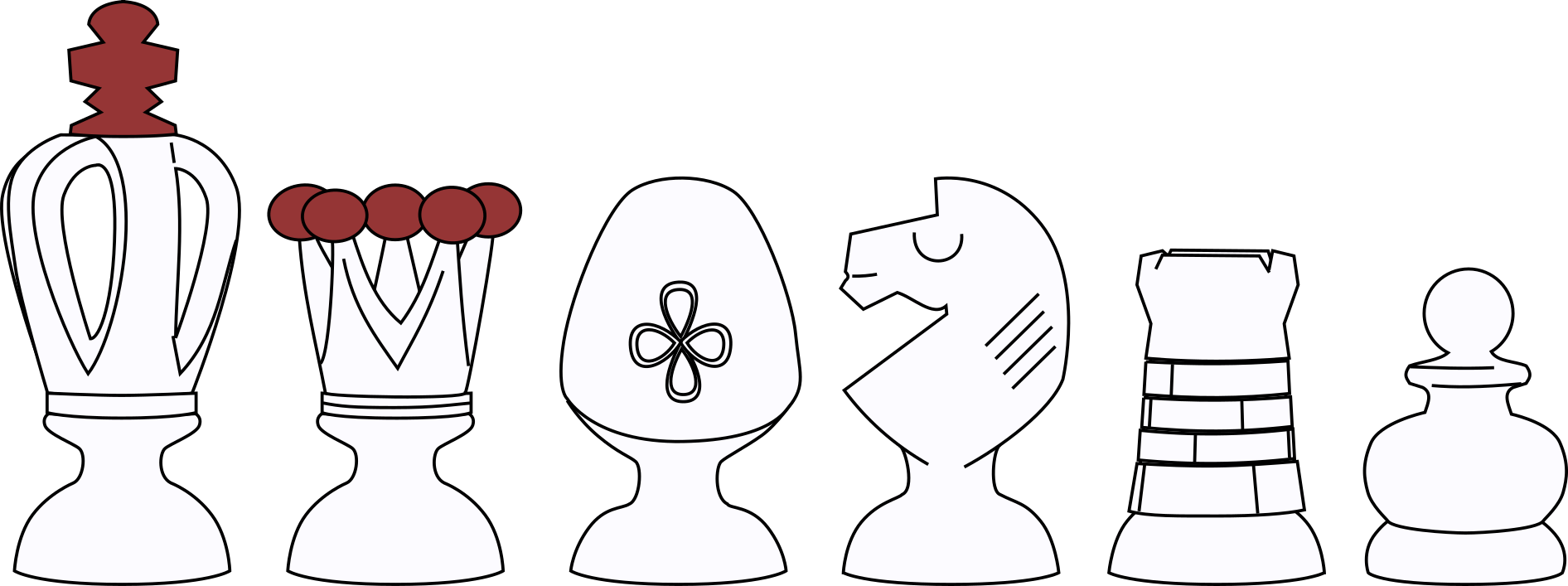

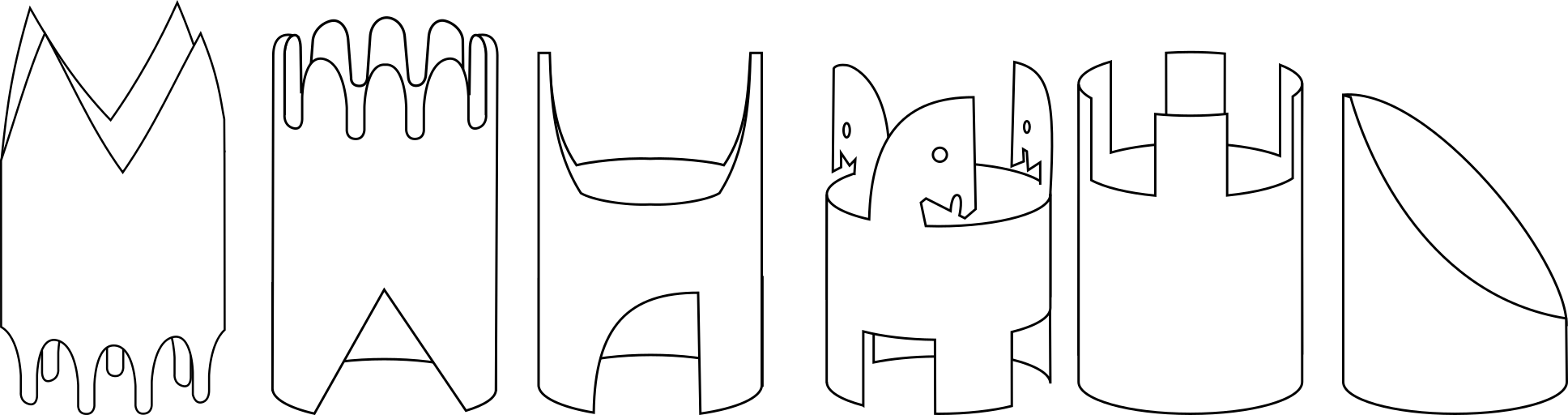

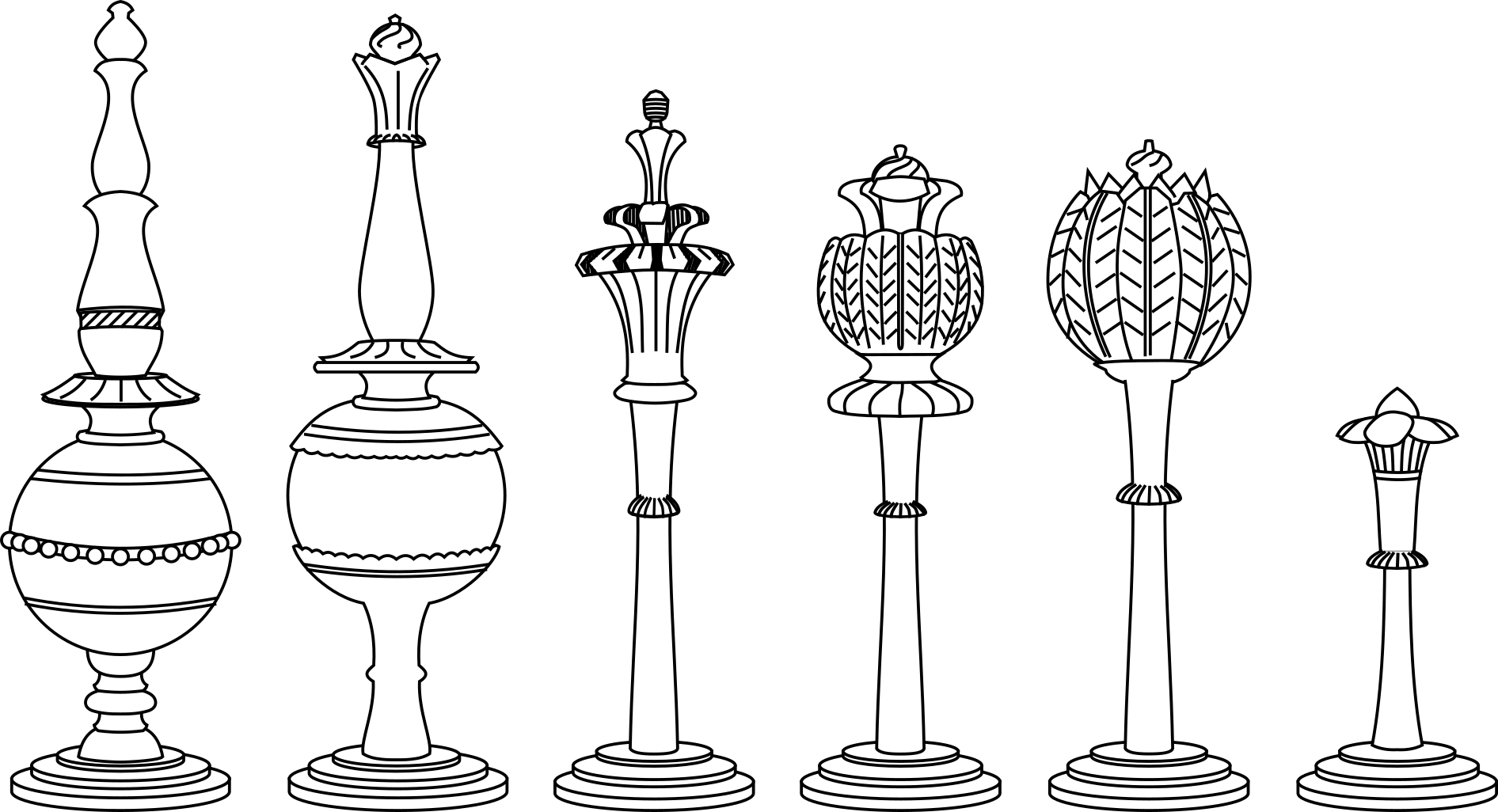

Crumiller gives his set of this design—though featuring horses as knights and turrets as rooks—the appellation Turkish Water Sprinklers and a date of c. 1900 . He justifies this thus:

Very few of these original antique sets are still around. The origins of this pattern are difficult to discern, but the king and queen pieces (especially those from several similiar extant sets) bear a strong resemblance to mid-to-late 19th-century water sprinklers that were made in Turkey, hence these sets are considered to be of Turkish origin and from approximately the same time period.

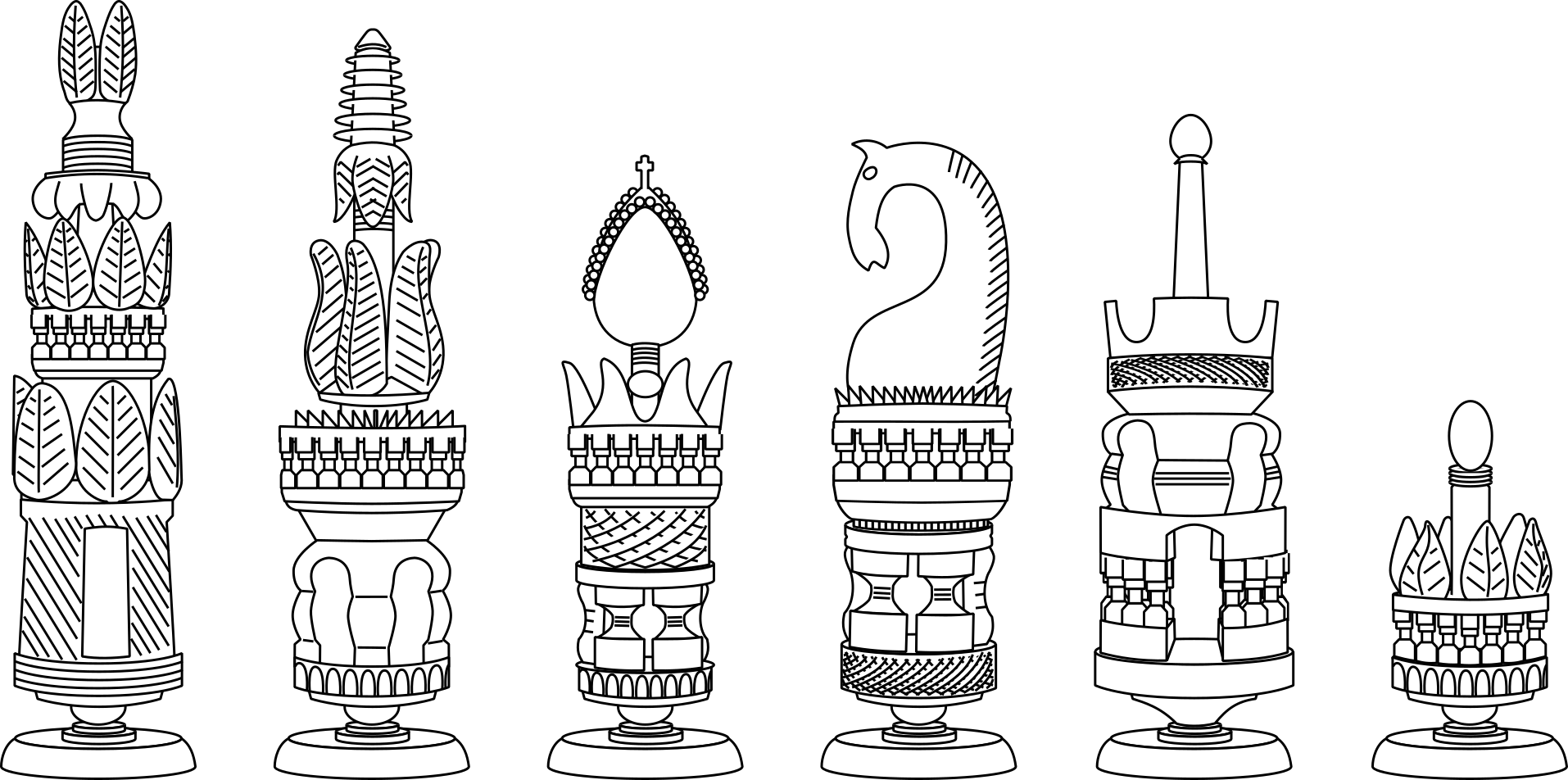

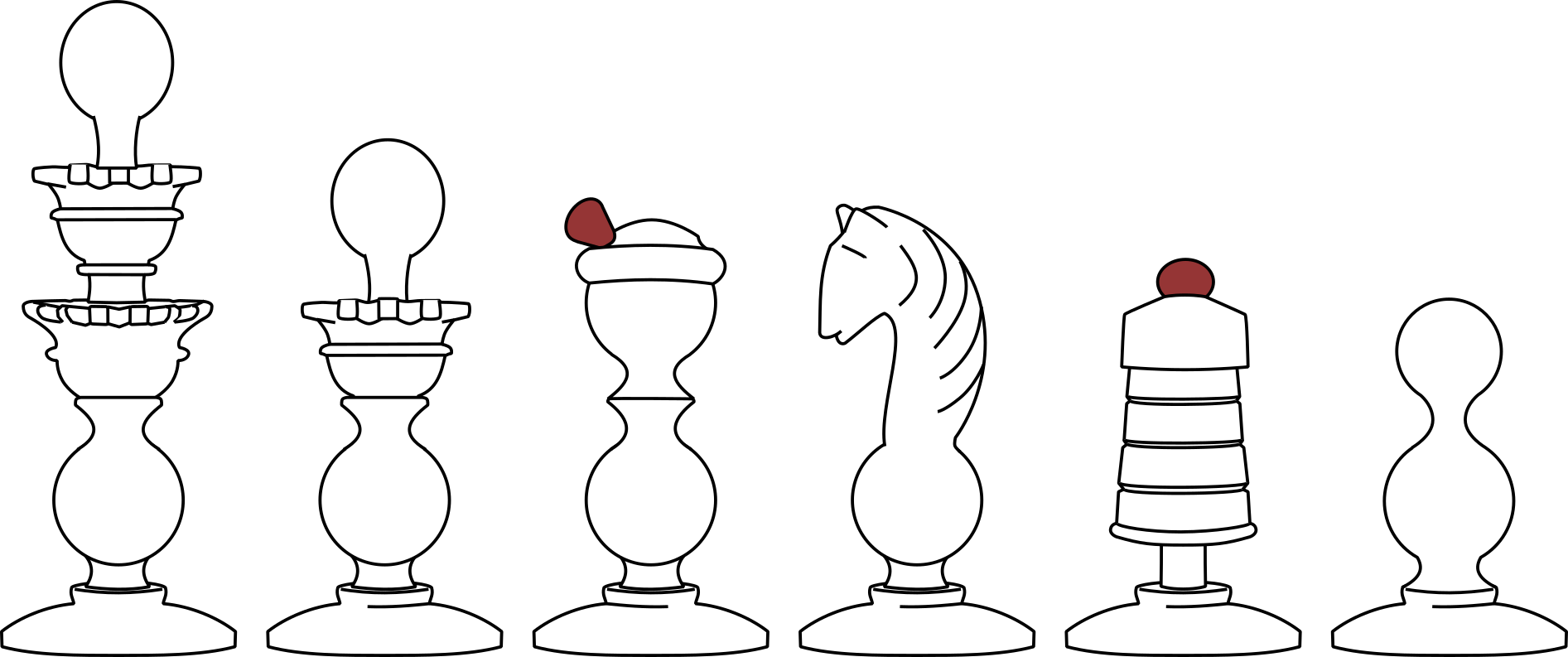

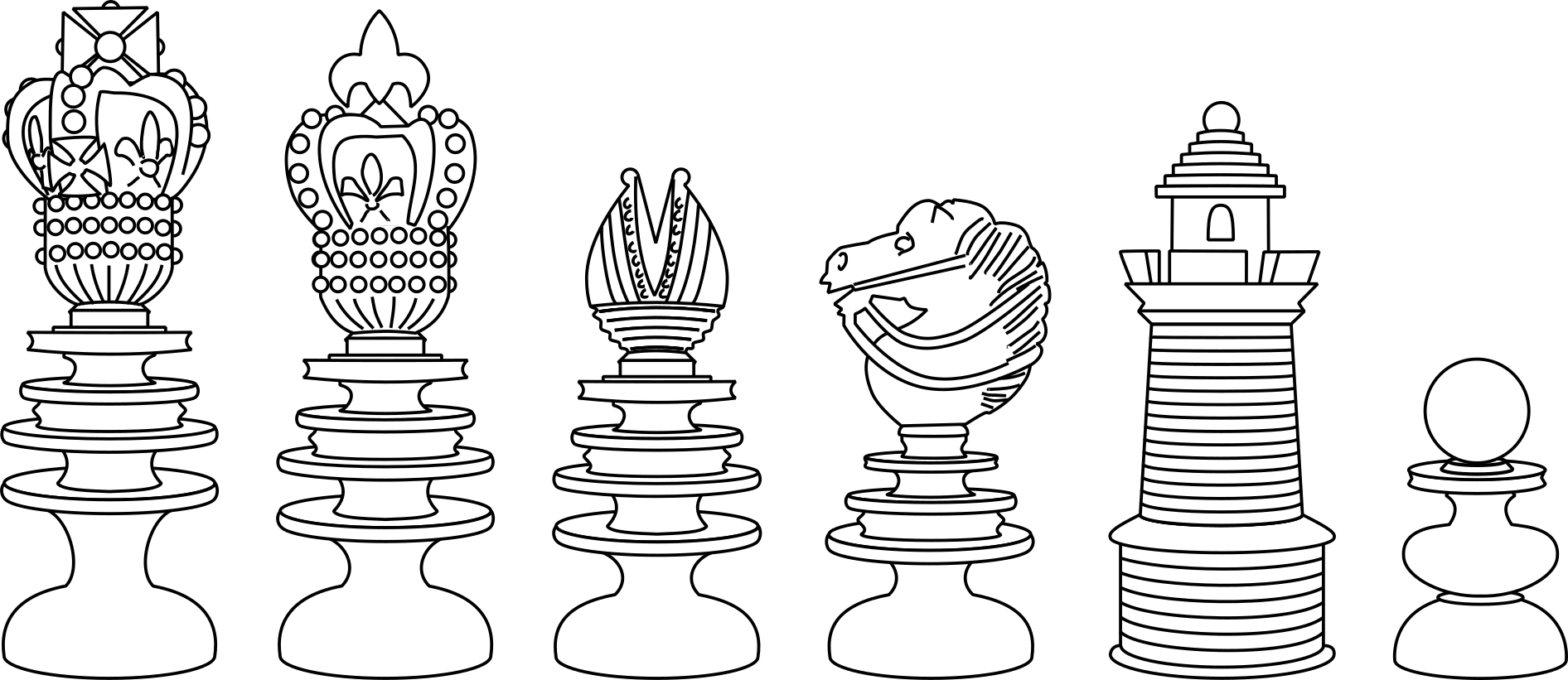

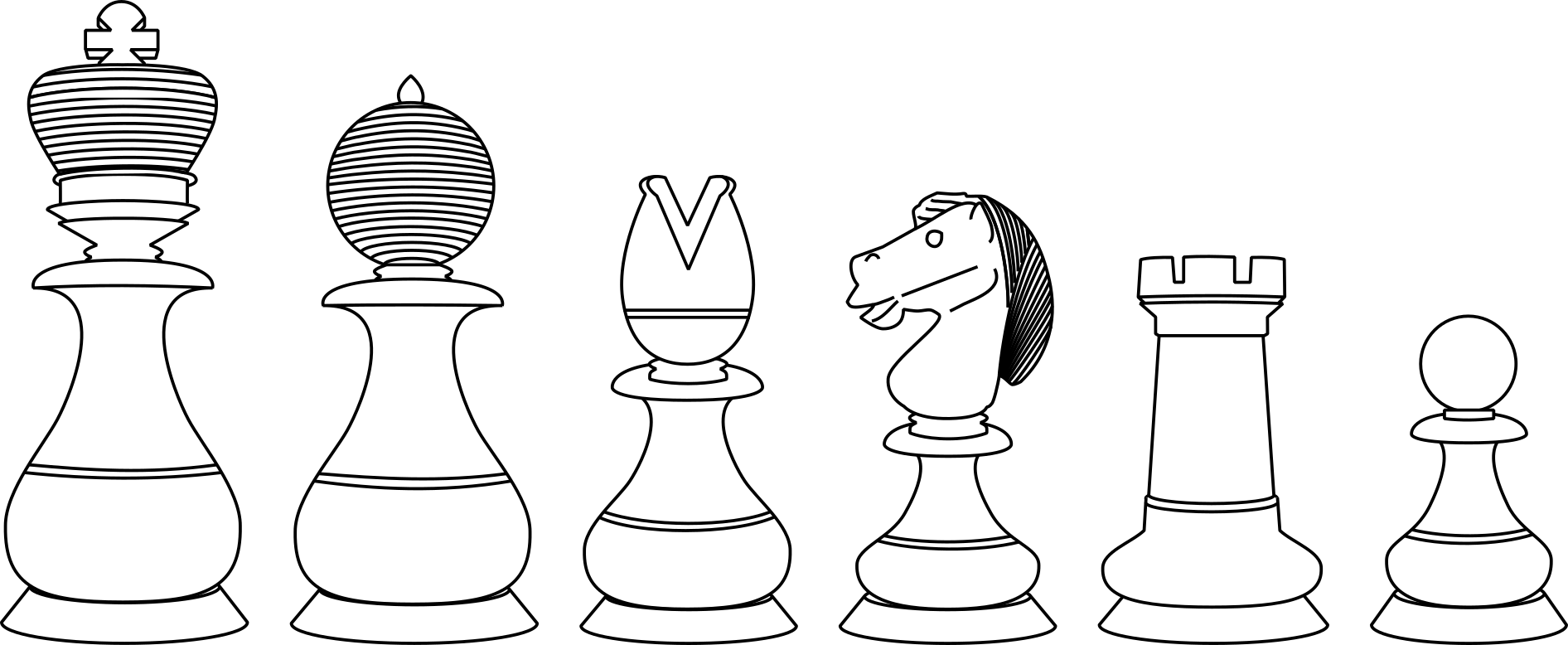

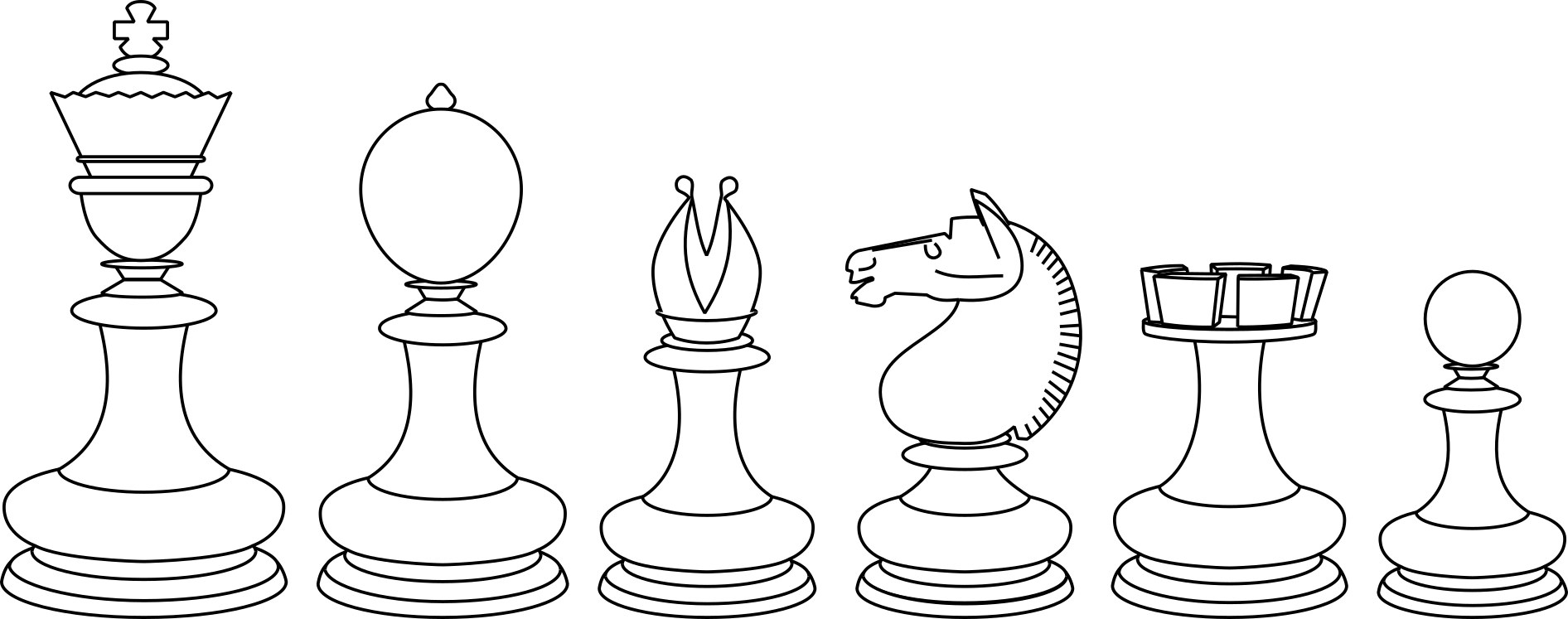

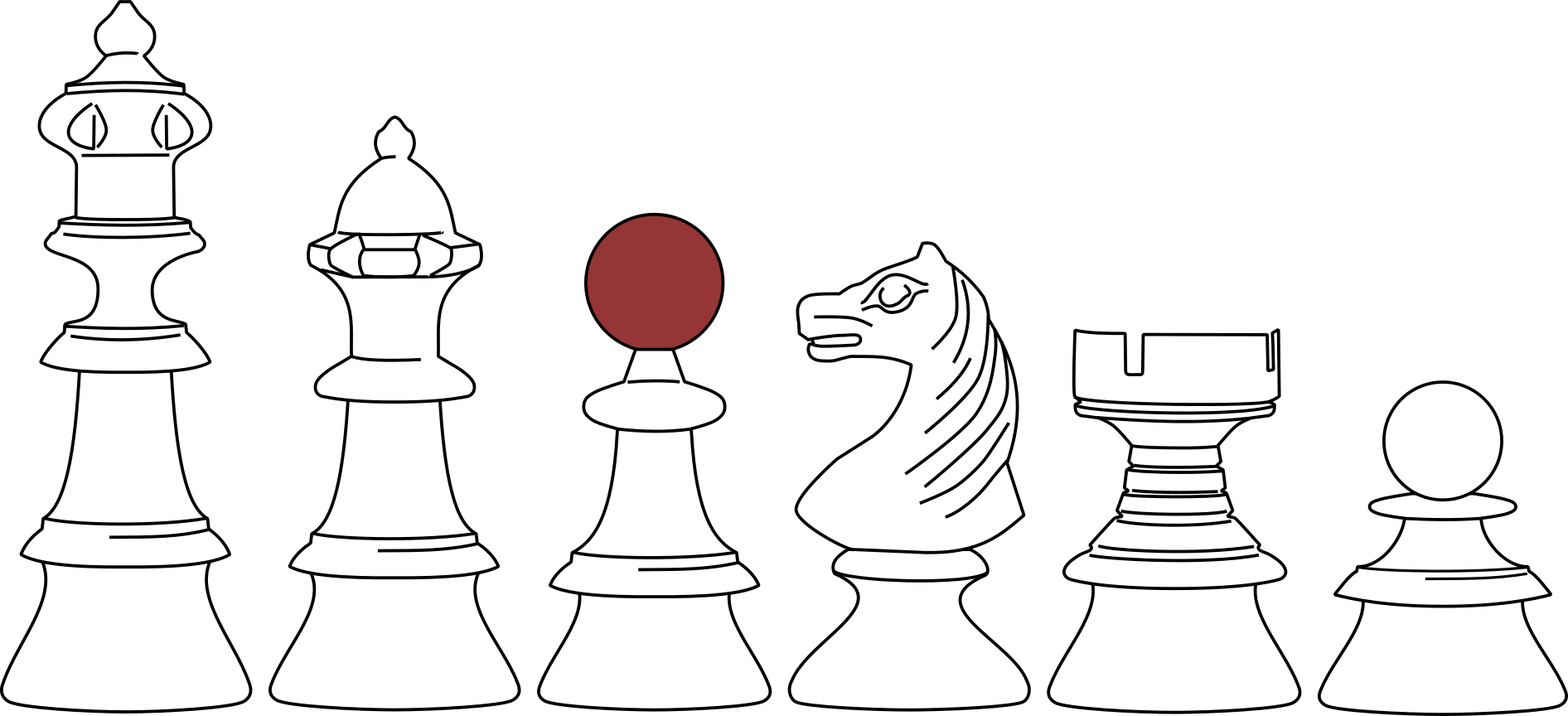

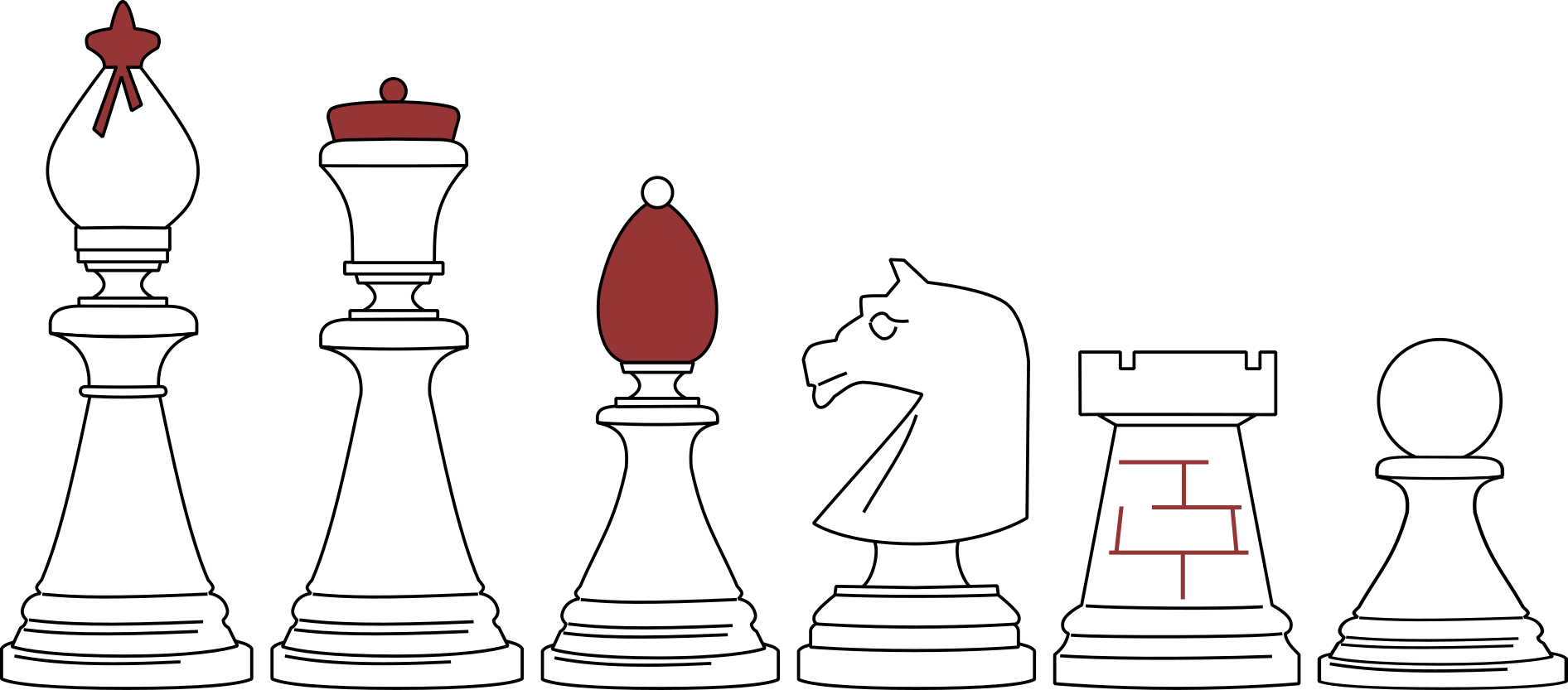

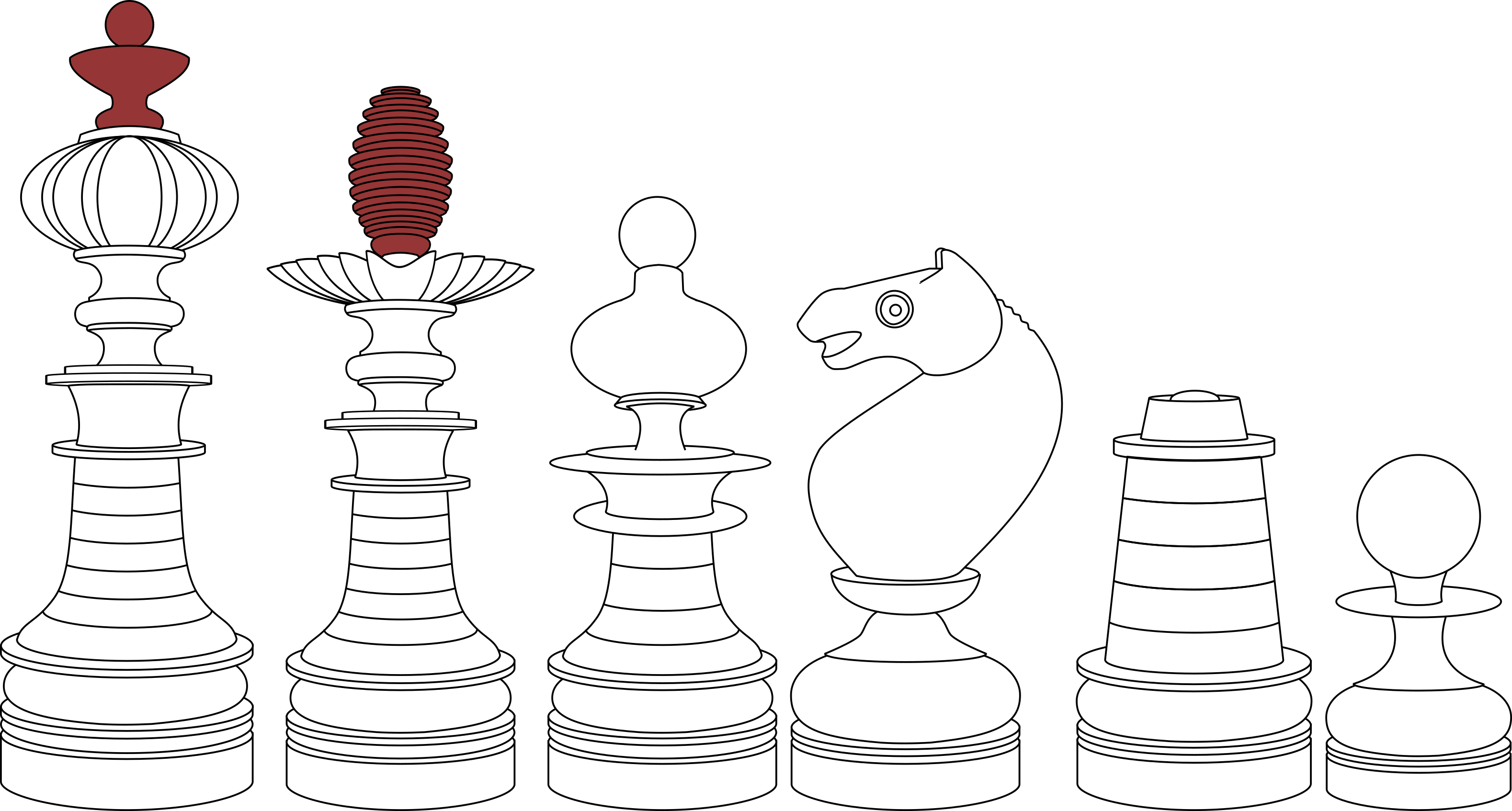

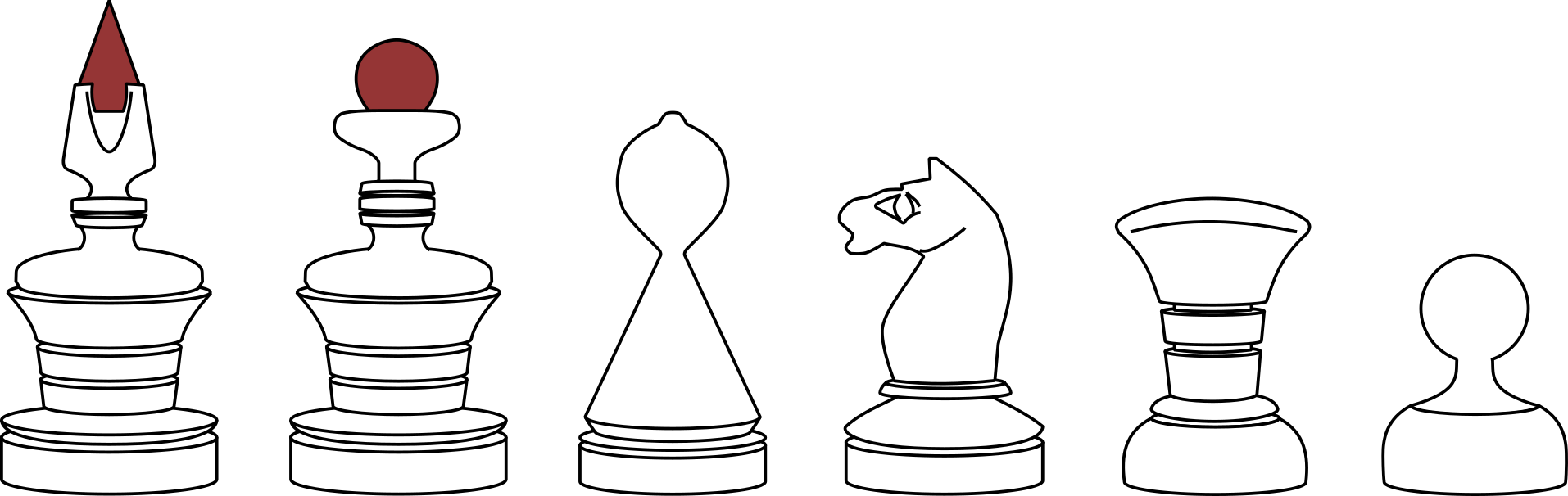

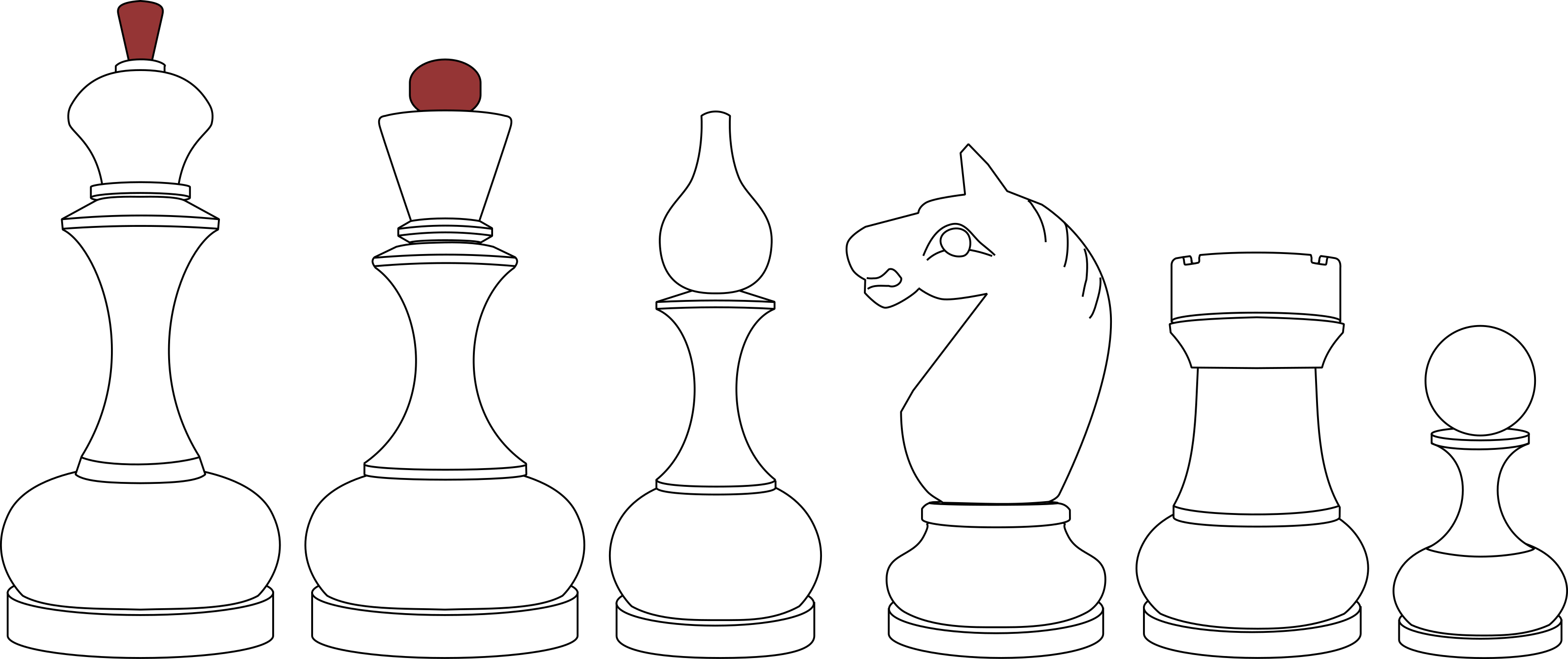

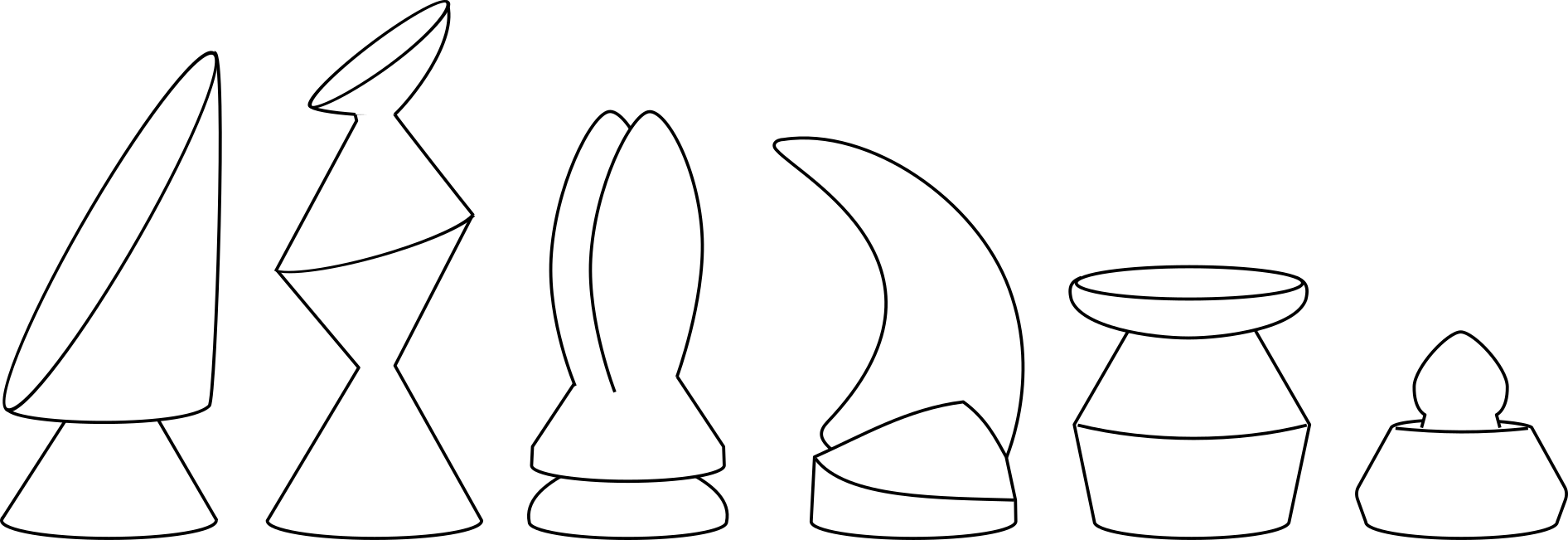

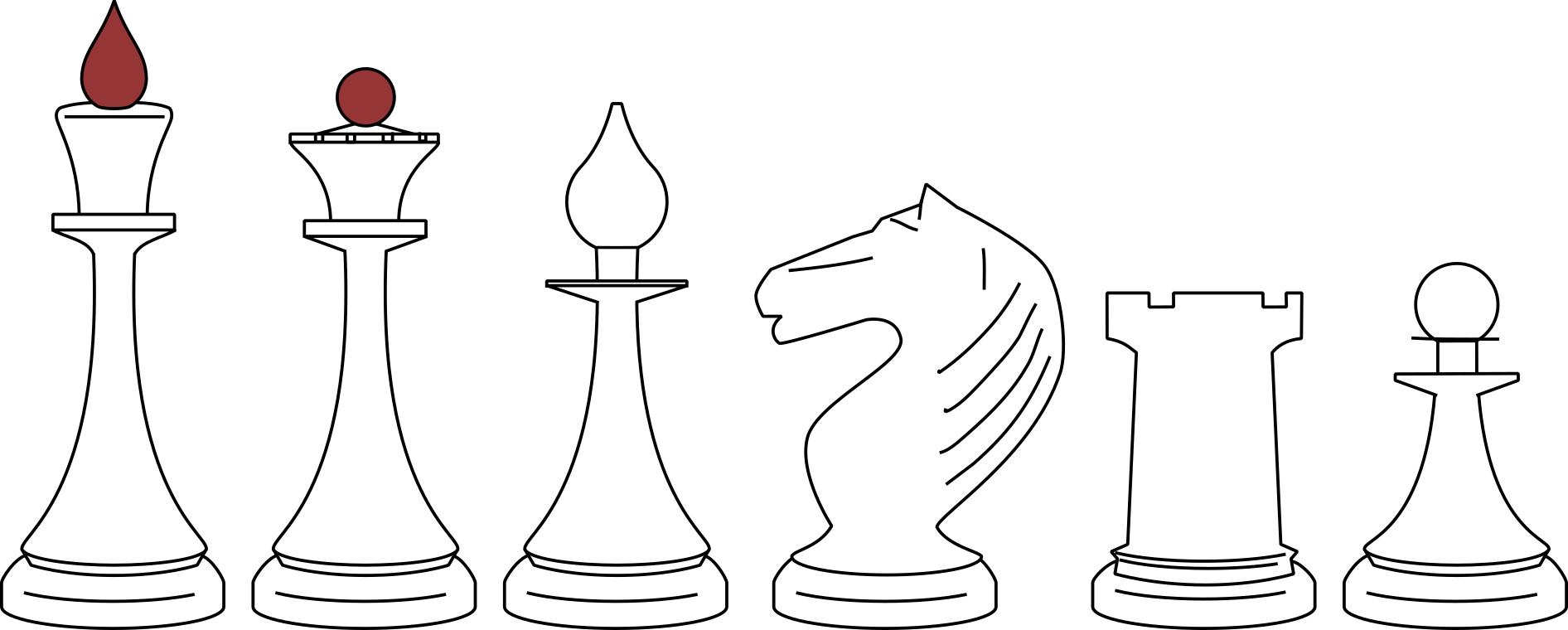

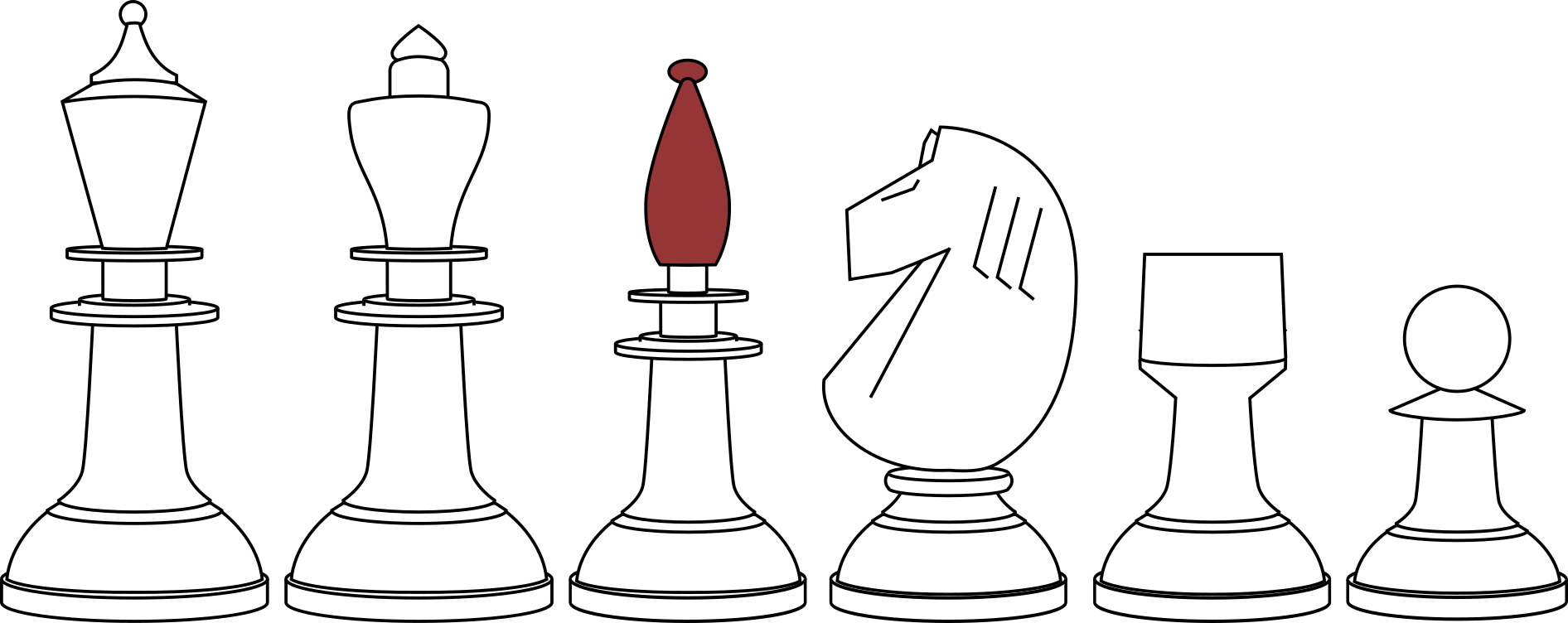

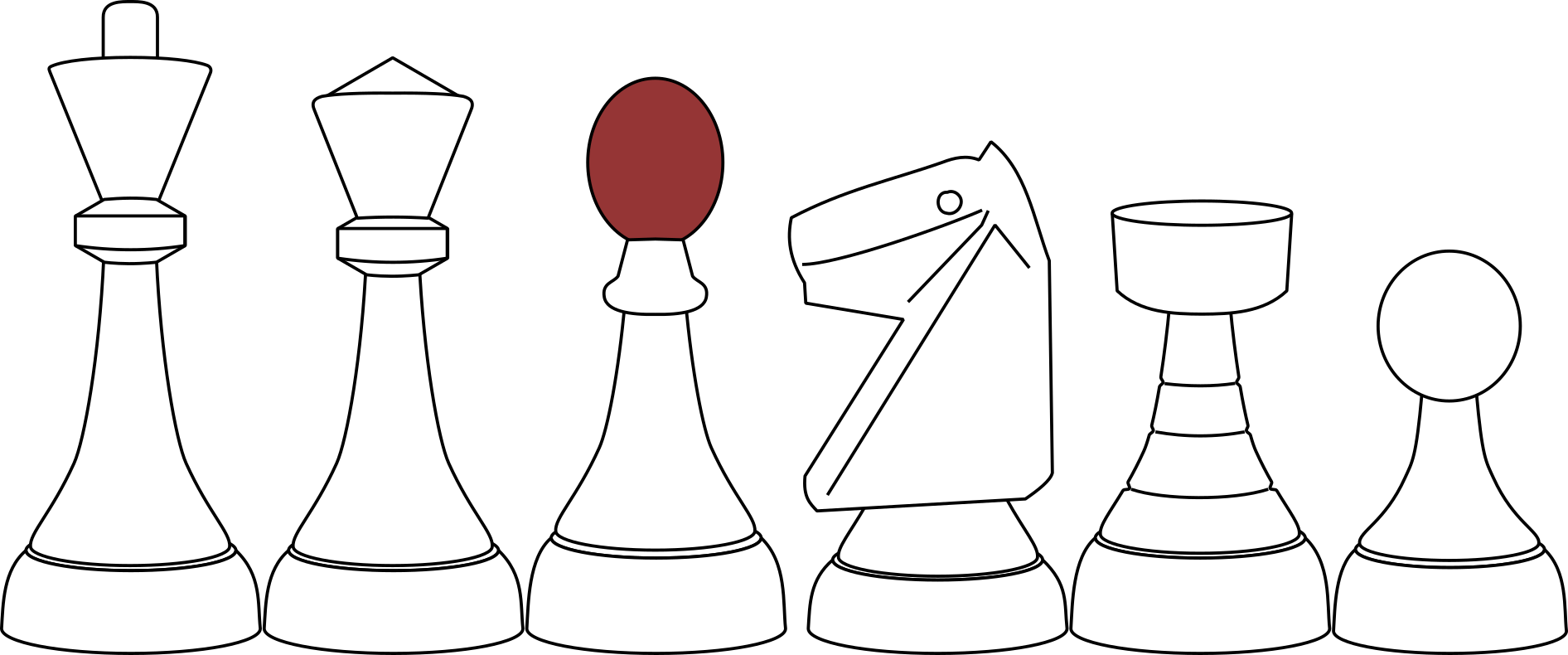

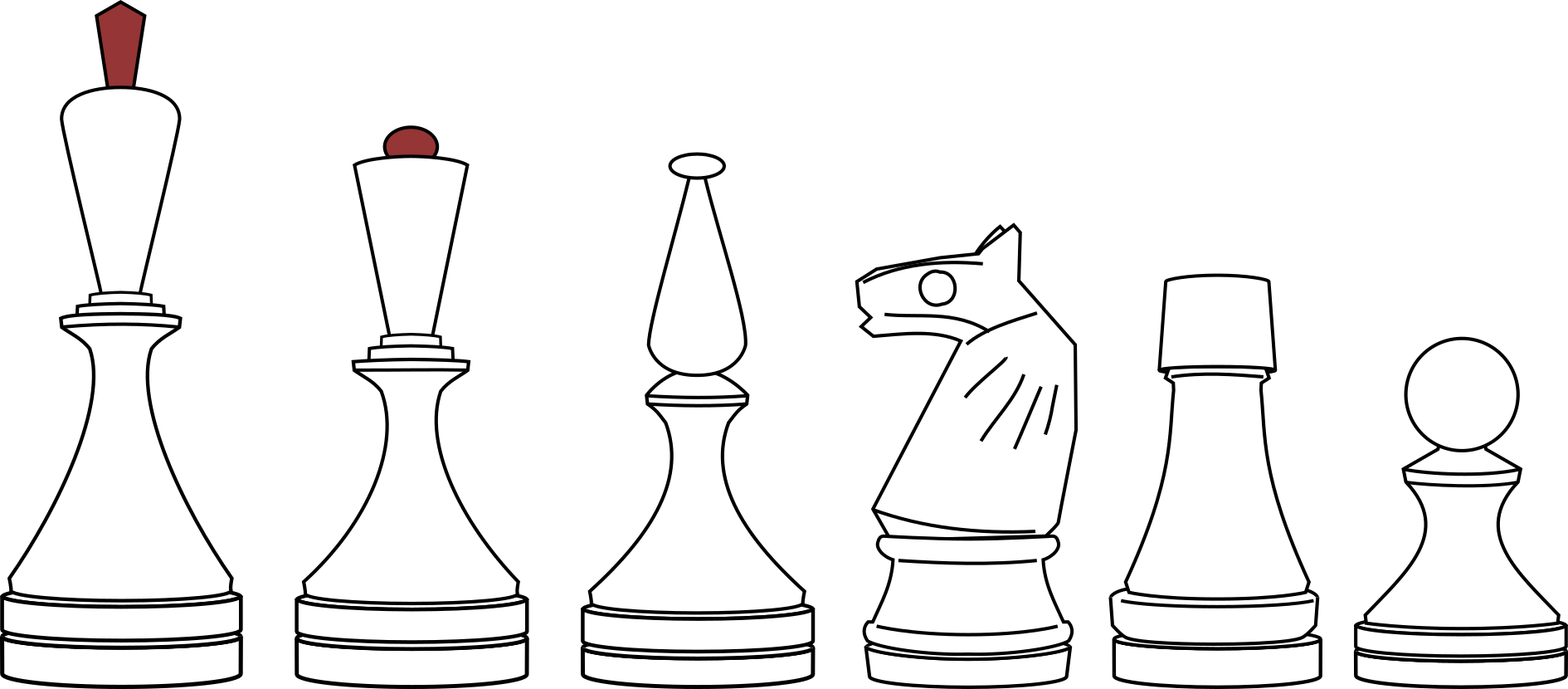

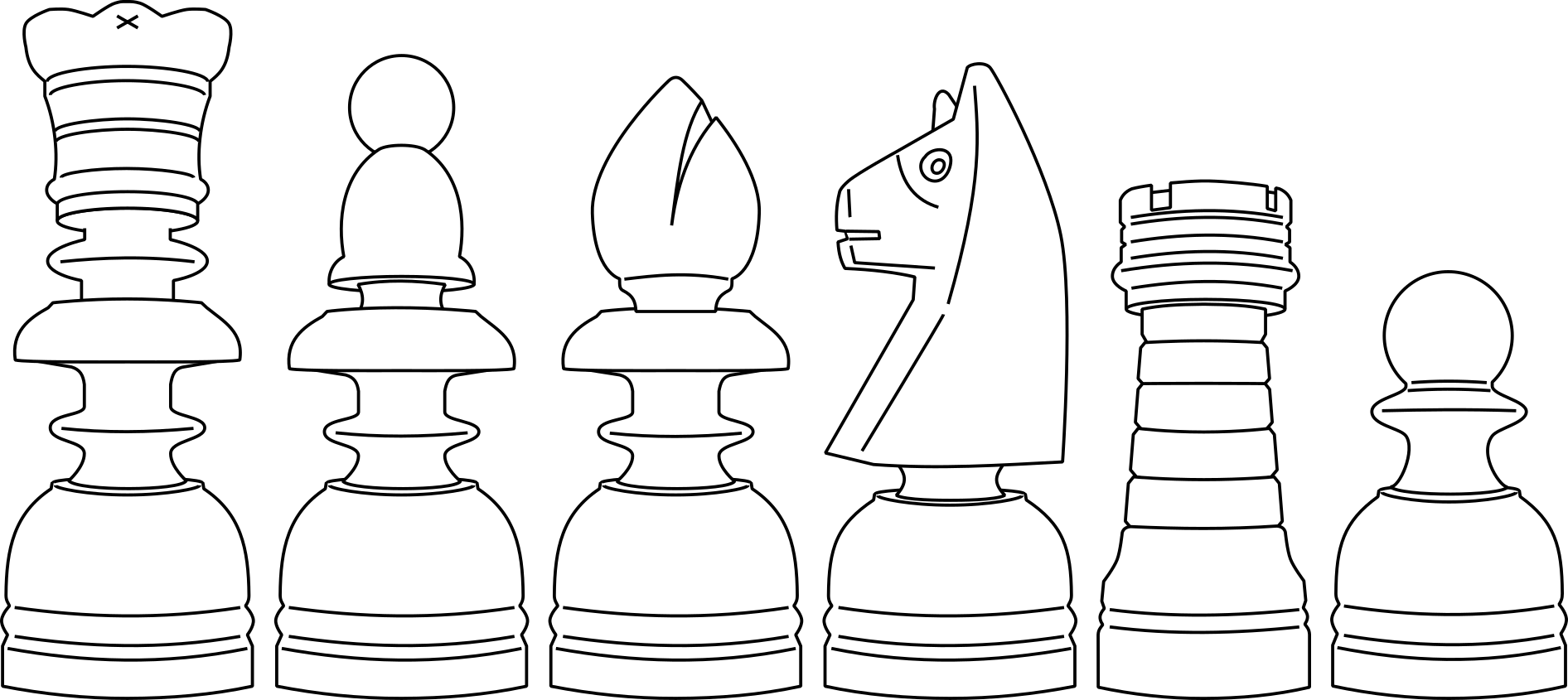

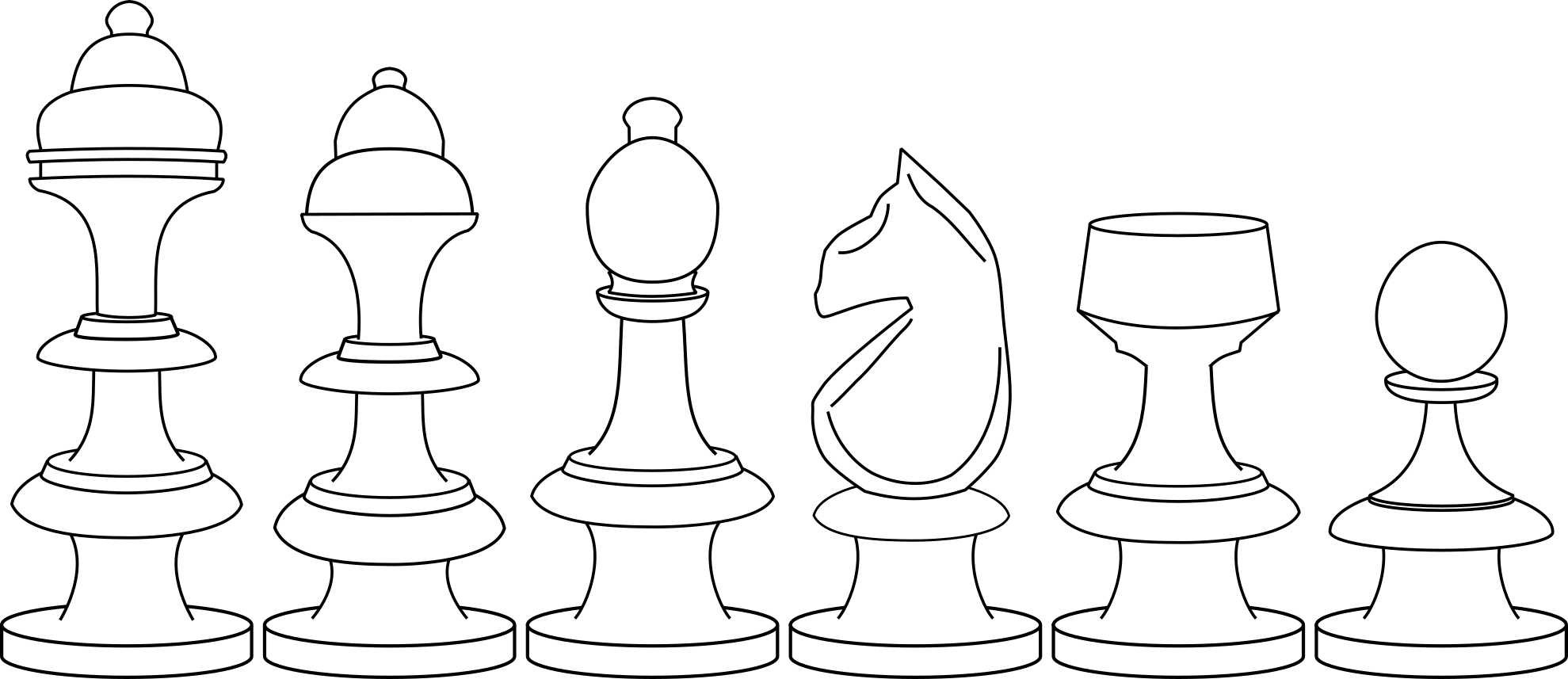

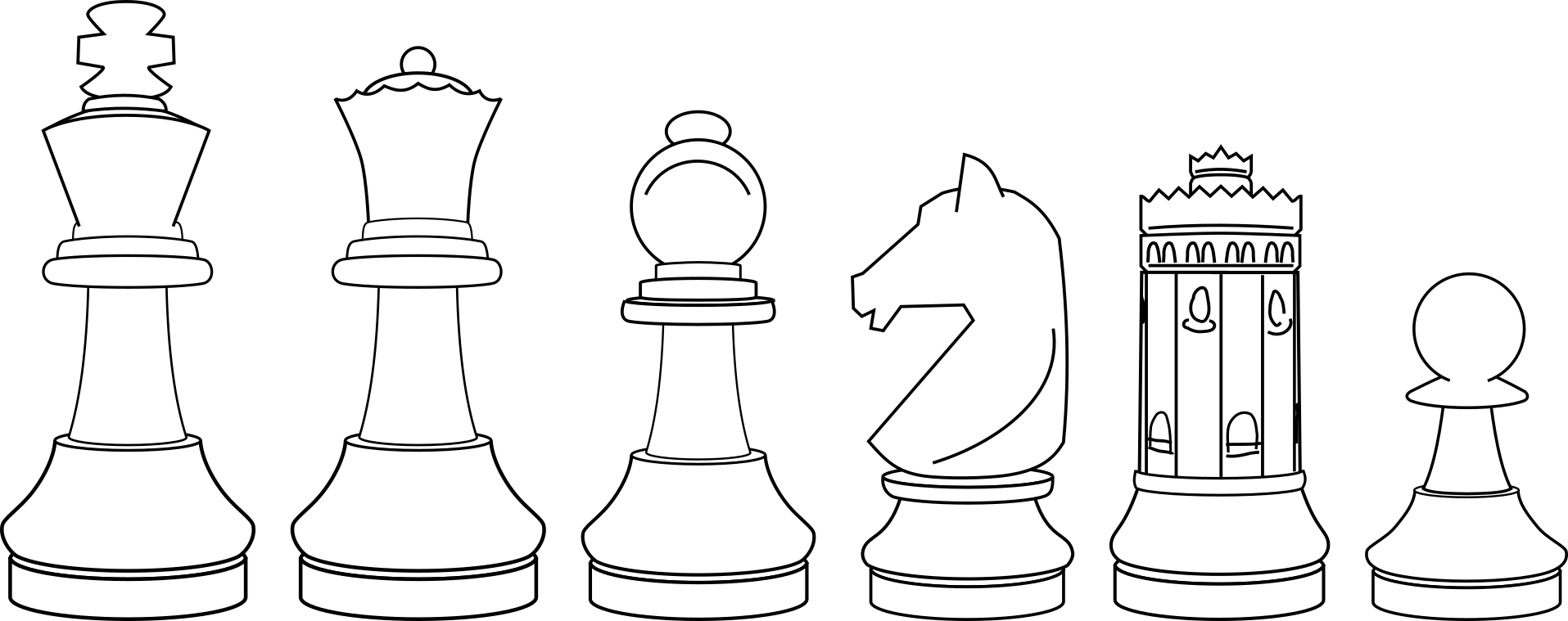

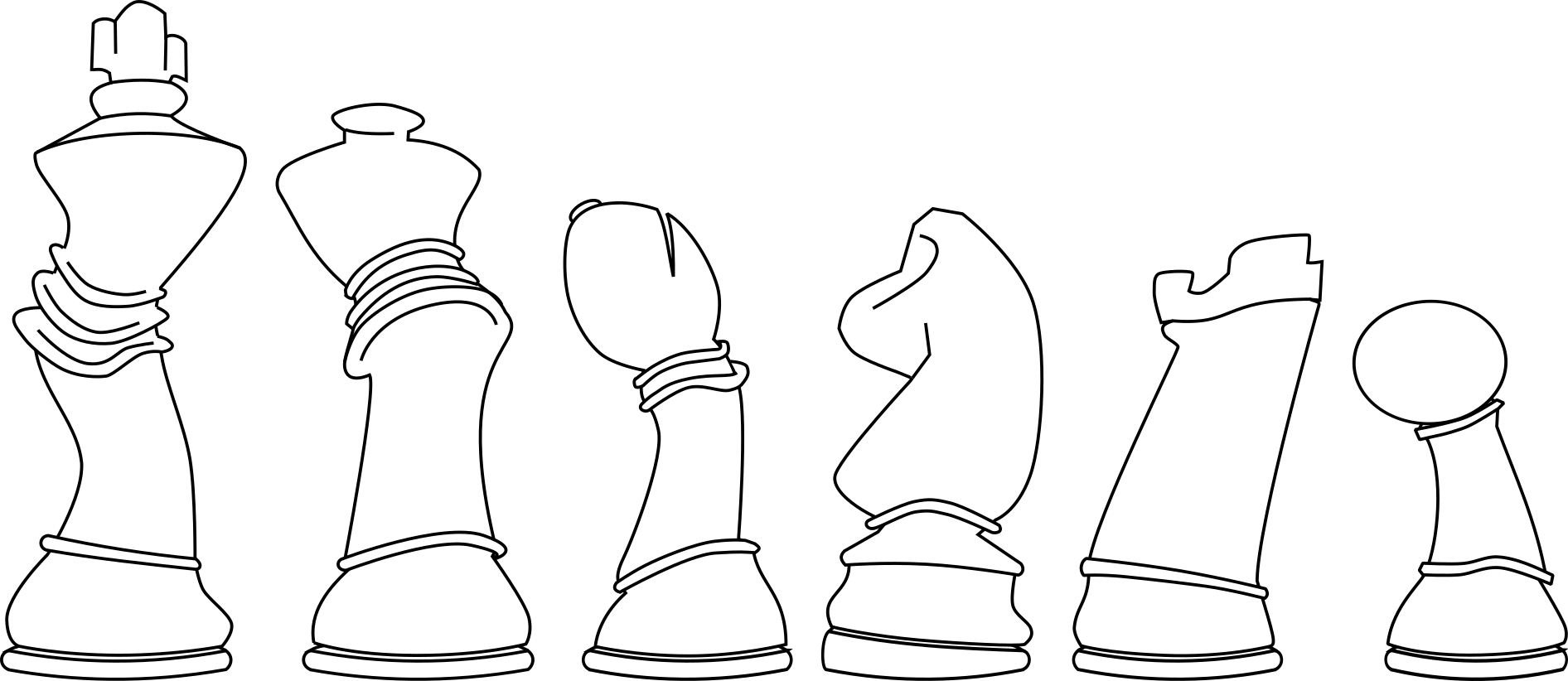

Crumiller notes that his set is unusual in having horses for knights and turrets for rooks, saying that others of the type have "floral-capped knights, and floral cups for rooks."

There are exactly two sets of this design that I have found auctioned as 1900 or earlier.

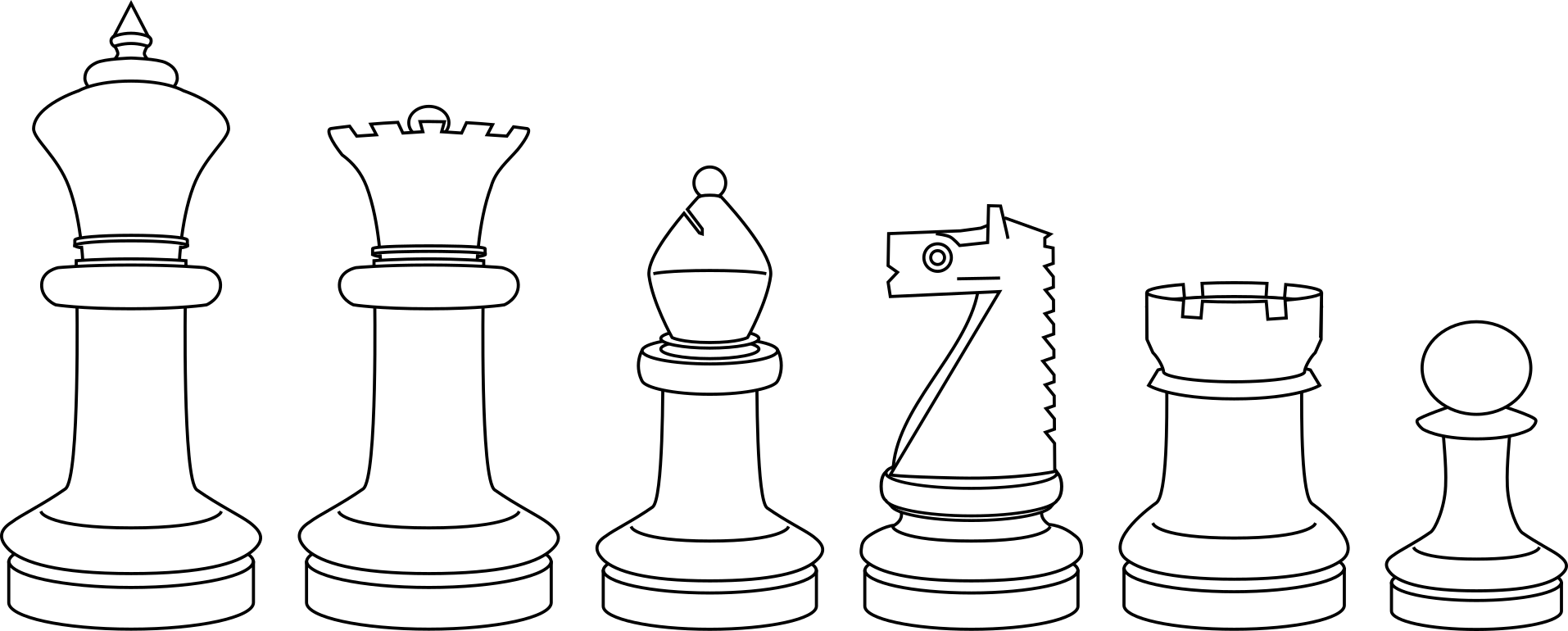

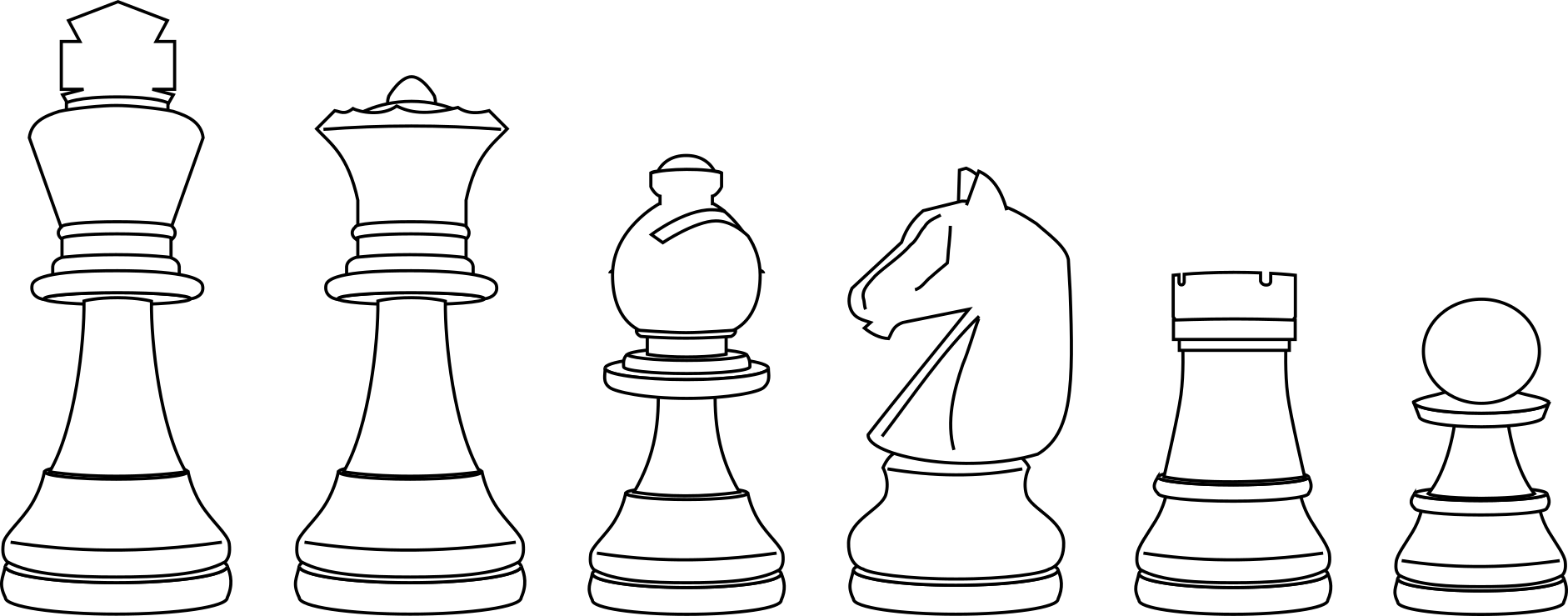

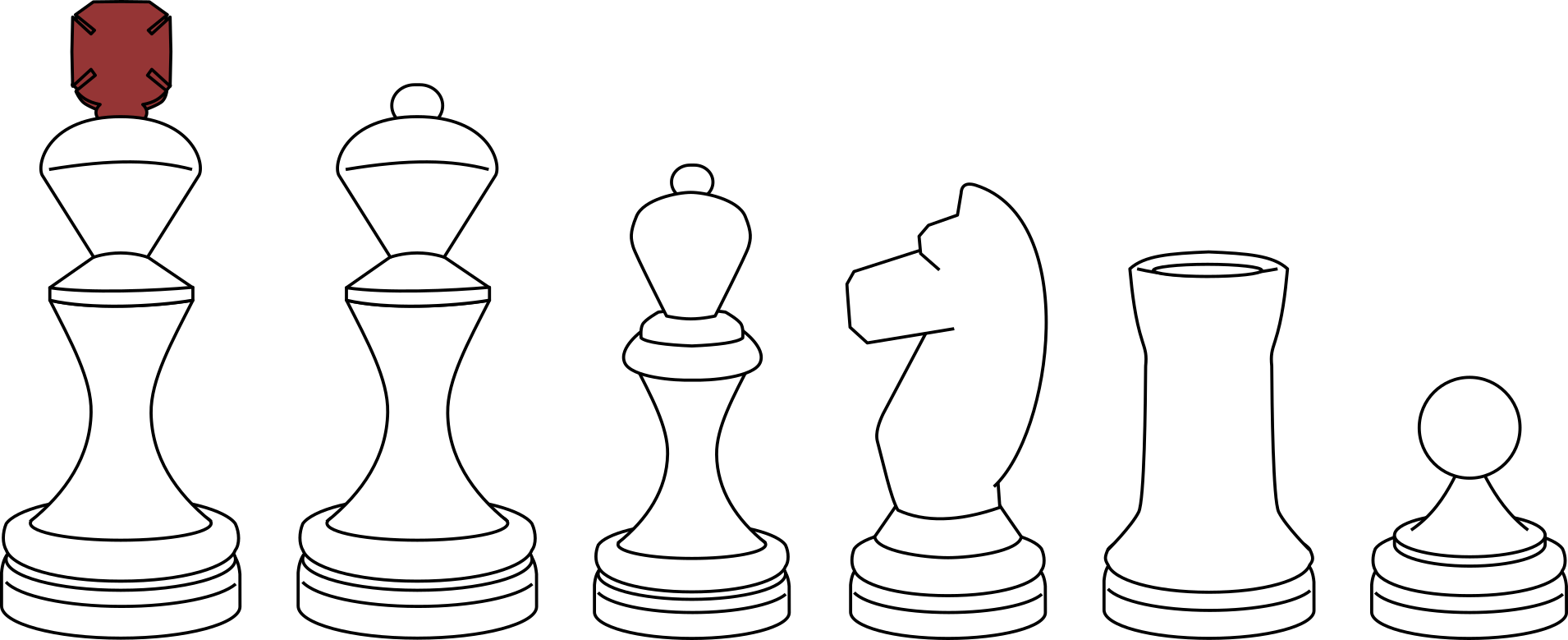

I am certain Crumiller's set (with horses and turrets) came from the Dr Jean-Claude Cholet Collection auction in 2007, where Christie's dated it as 1900 and described it as (without further explanation).

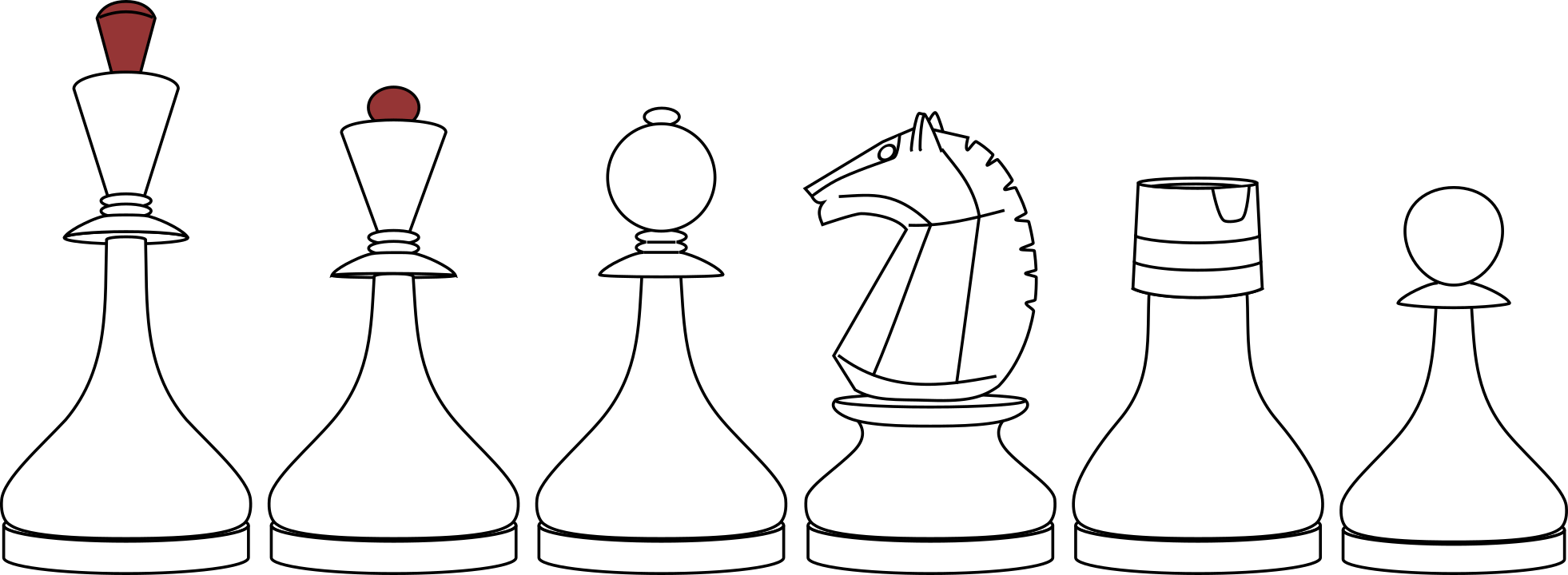

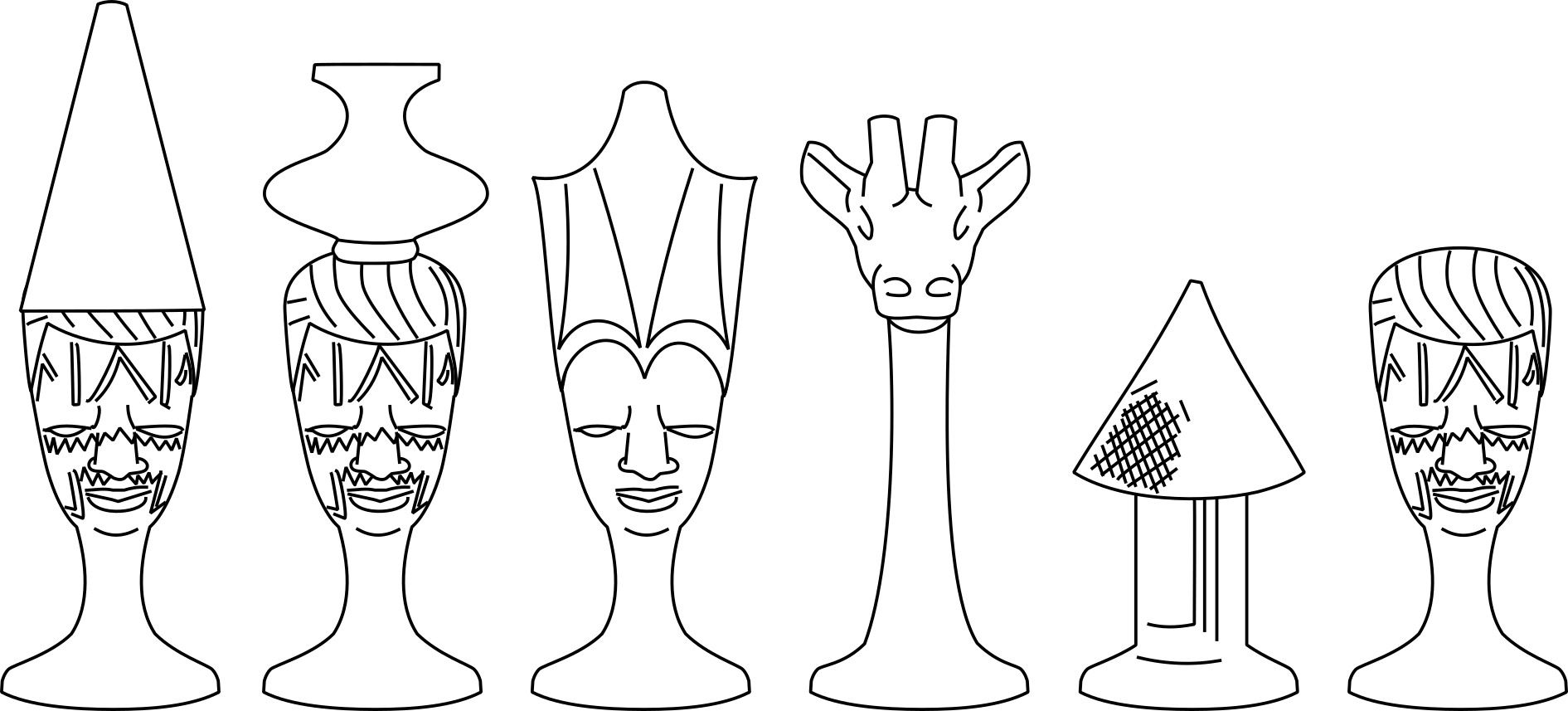

Another example, from the Bronstein collection, was where it was also attributed to the Ottoman Empire and dated 19th Century. This one had floral knights and rooks. Like the Cholet/Crumiller set, it is white and stained-green ivory. These two sets, the Bronstein set and the Cholet/Crumiller set, are the only instances of this pattern that I have found auctioned as 1900 or earlier.

I don't find the "water sprinkler" explanation to be a compelling argument that these must have a Turkish origin (or a 1900 date) for all sorts of reasons.

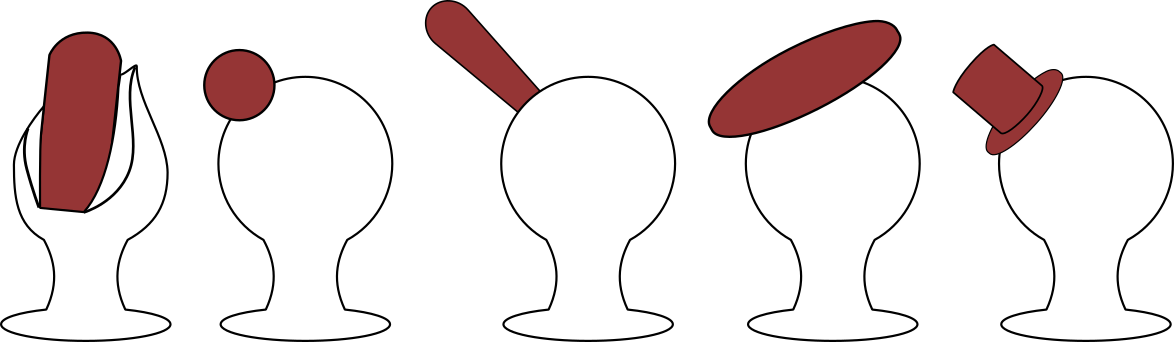

Firstly, if we accept that the King and Queen were based on Turkish rose water sprinklers, that does not necessarily mean that this design originated in Türkiye as opposed to anywhere else where they had seen such sprinklers. Rose water sprinklers are not made on a lathe anyway, so there's no reason to suppose it would need to be the same workmen with the same skills producing both.

Secondly, rose water sprinklers are not uniquely Turkish. Many fine examples come from 18th (e.g.) and 19th (e.g.) Century India. So, if we accept that the King and Queen were based on rose water sprinklers, we would do as well to say that this supports an 18th or 19th Century Indian origin.

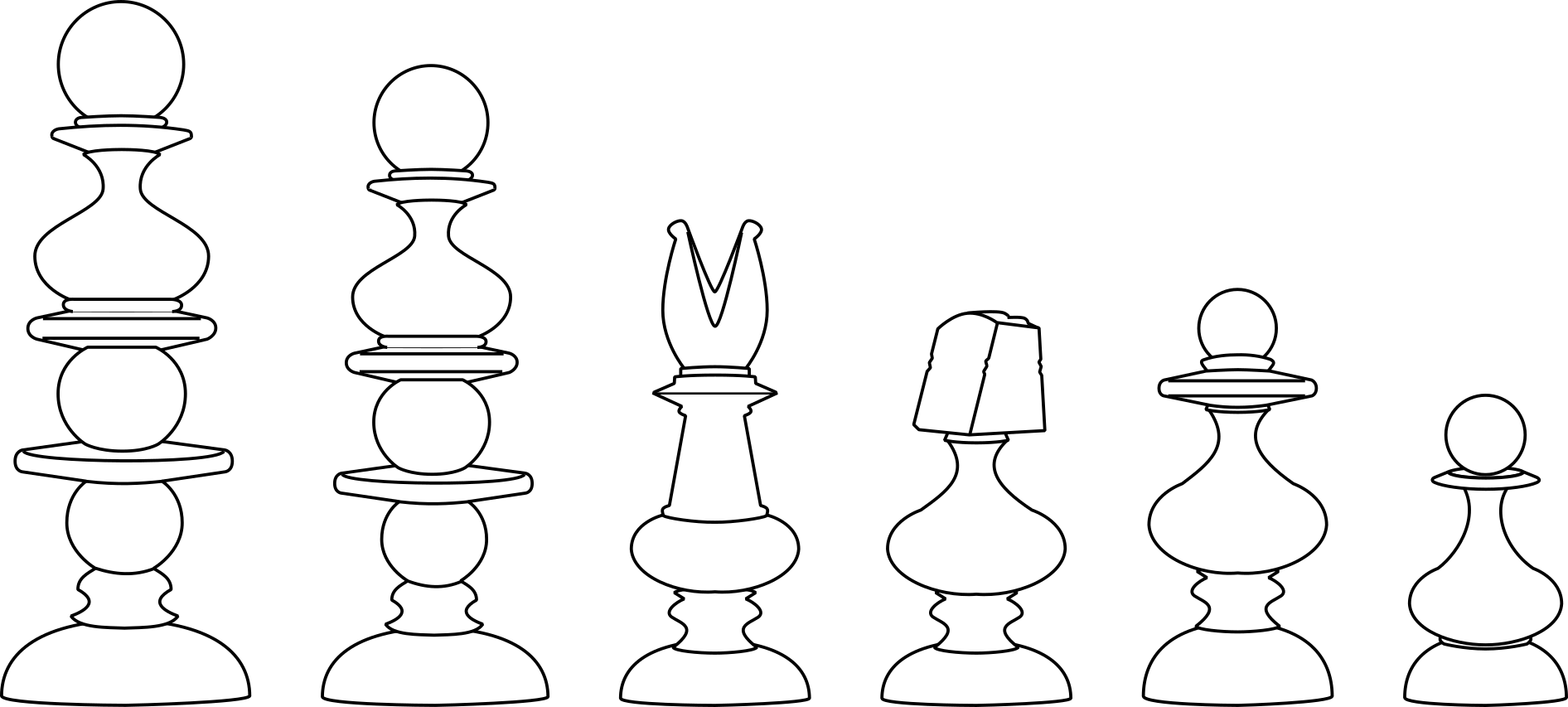

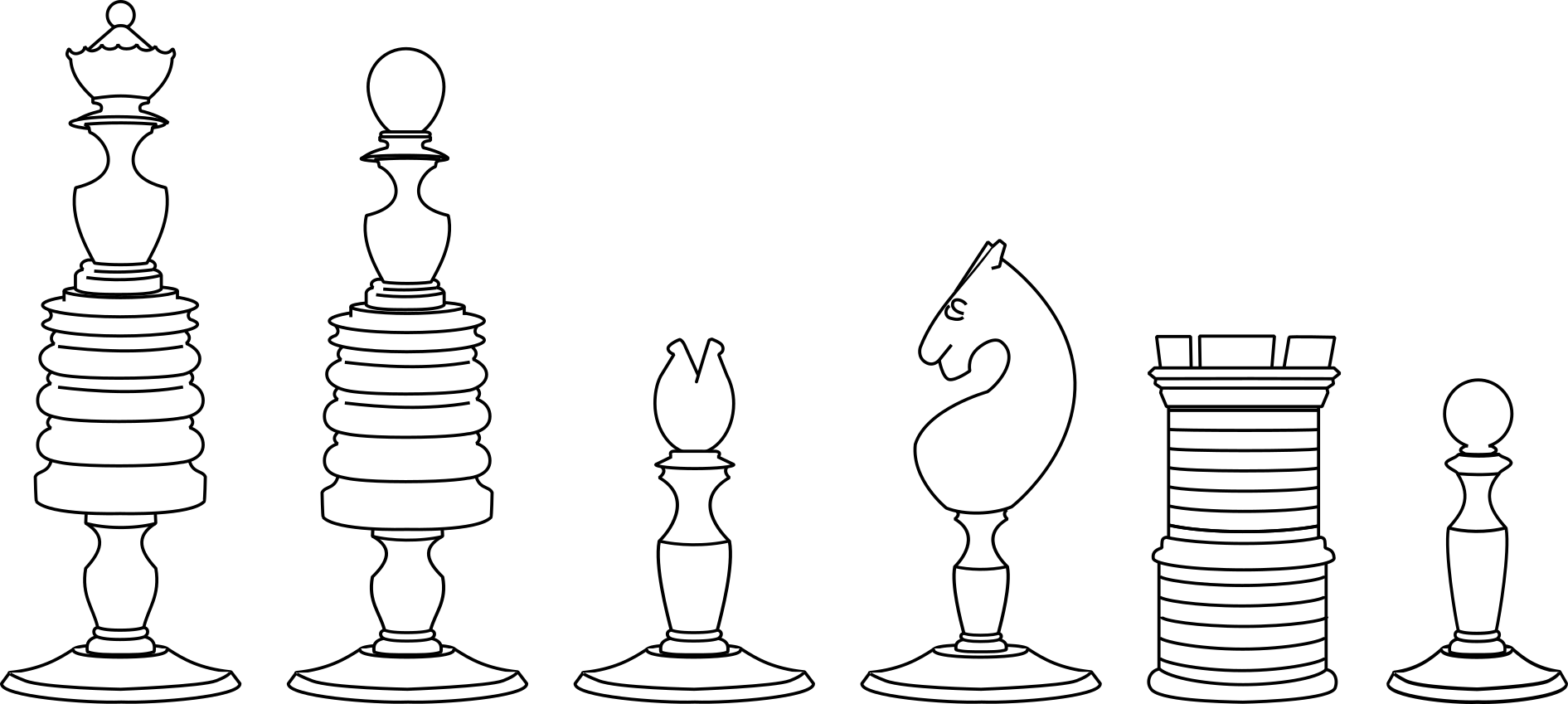

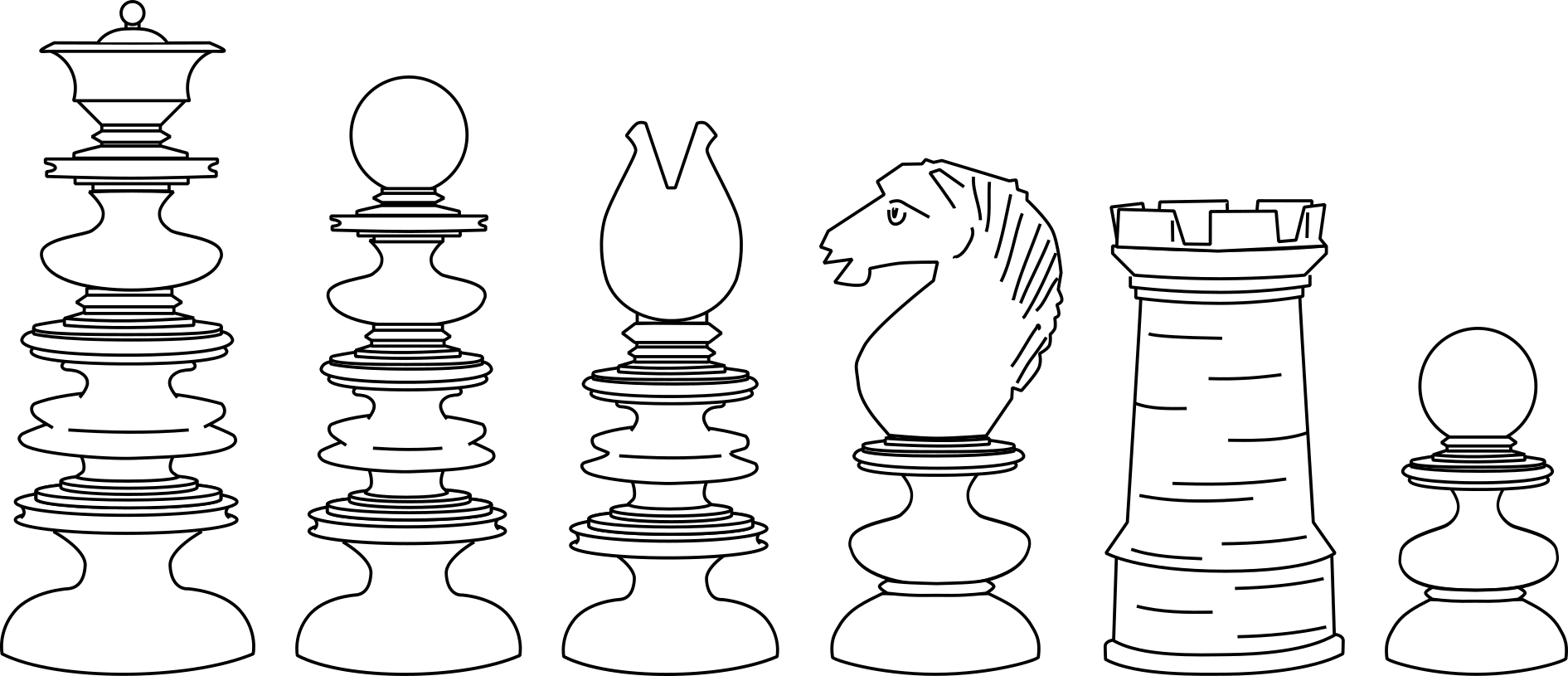

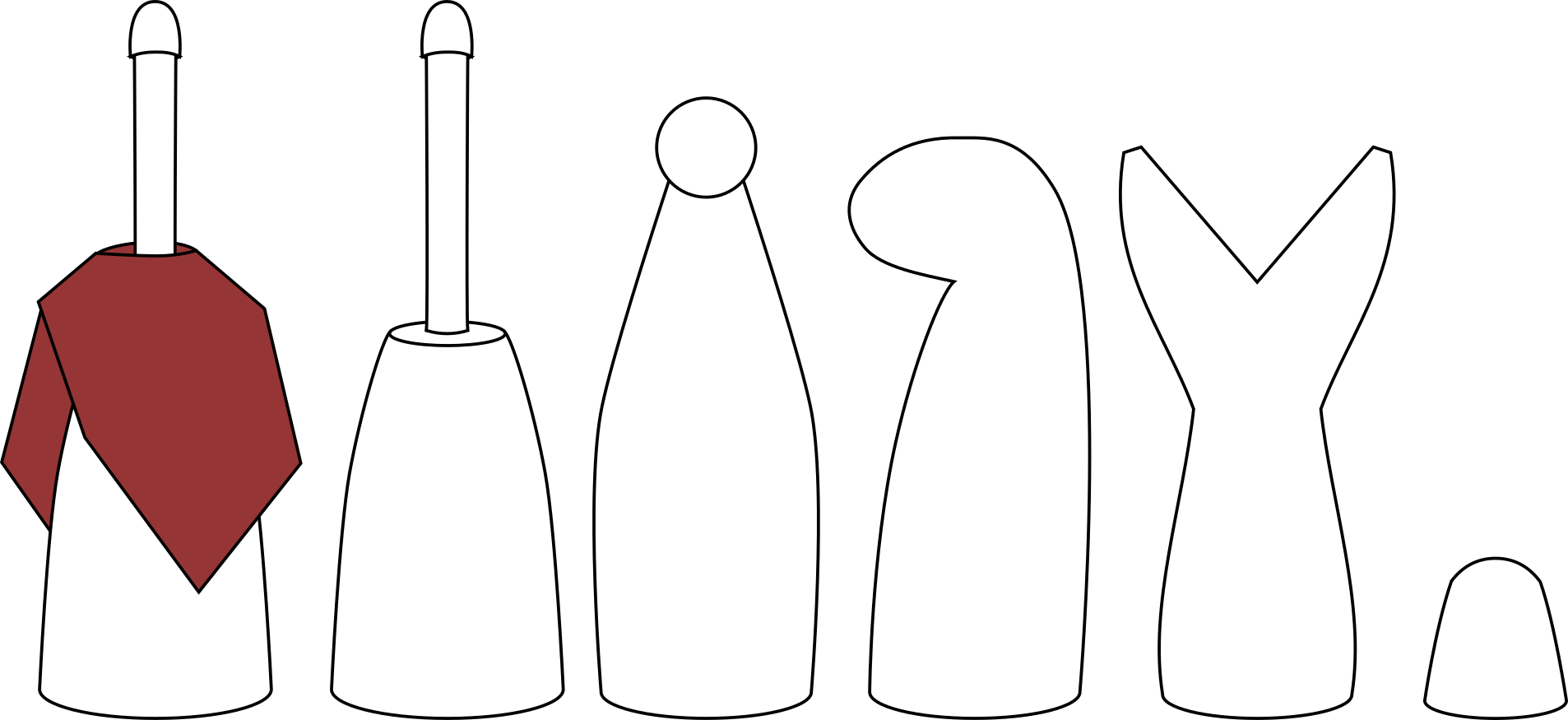

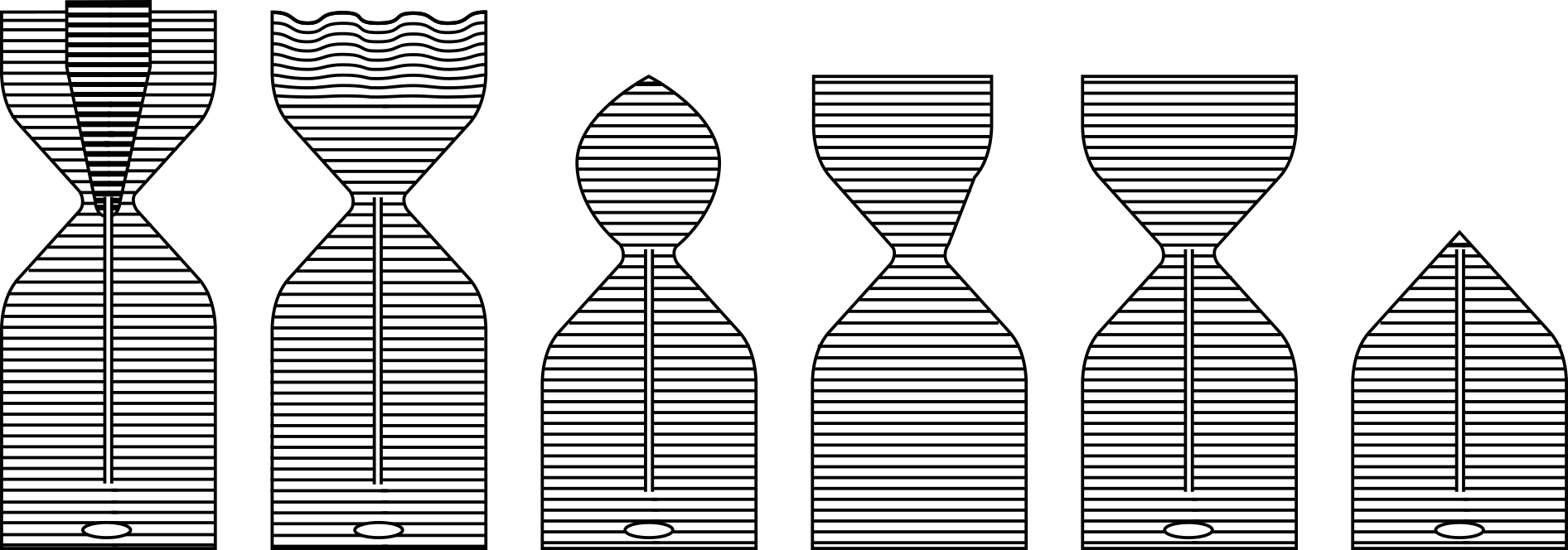

But do we accept that the King and Queen were based on rose water sprinklers? Just because the King and Queen evoke rose water sprinklers does not actually mean their designers were inspired by such sprinklers. A bulb-shaped chess piece is not so unusual or distinctive a design. Their silhouette is the same in essentials as the King and Queen of Archangel sets produced in 18th Century Kholmogory (above). Many Anglo-Indian sets feature similar bulb shapes (the pawns of the so-called Pepys set, and others), as well as floral accents.

Put another way, I may look at cinder toffee and say "this reminds me of honeycomb," and that's perfectly valid, but it does not mean cinder toffee is made by bees.

Before we look at the origin of the Turkish water sprinkler claim (which will suggest to you a particular reading of this whole issue), let's first consider where else in the 19th Century such chess sets could have been made.

The non-figural nature of the pattern may suggest an Islamic design (which would including Ottoman of course). Aniconism associated with Islamic art avoids the depiction of people and animals, but floral designs avoid this prohibition. However, this becomes hard to reconcile with the Cholet/Crumiller set with its knights as horses.

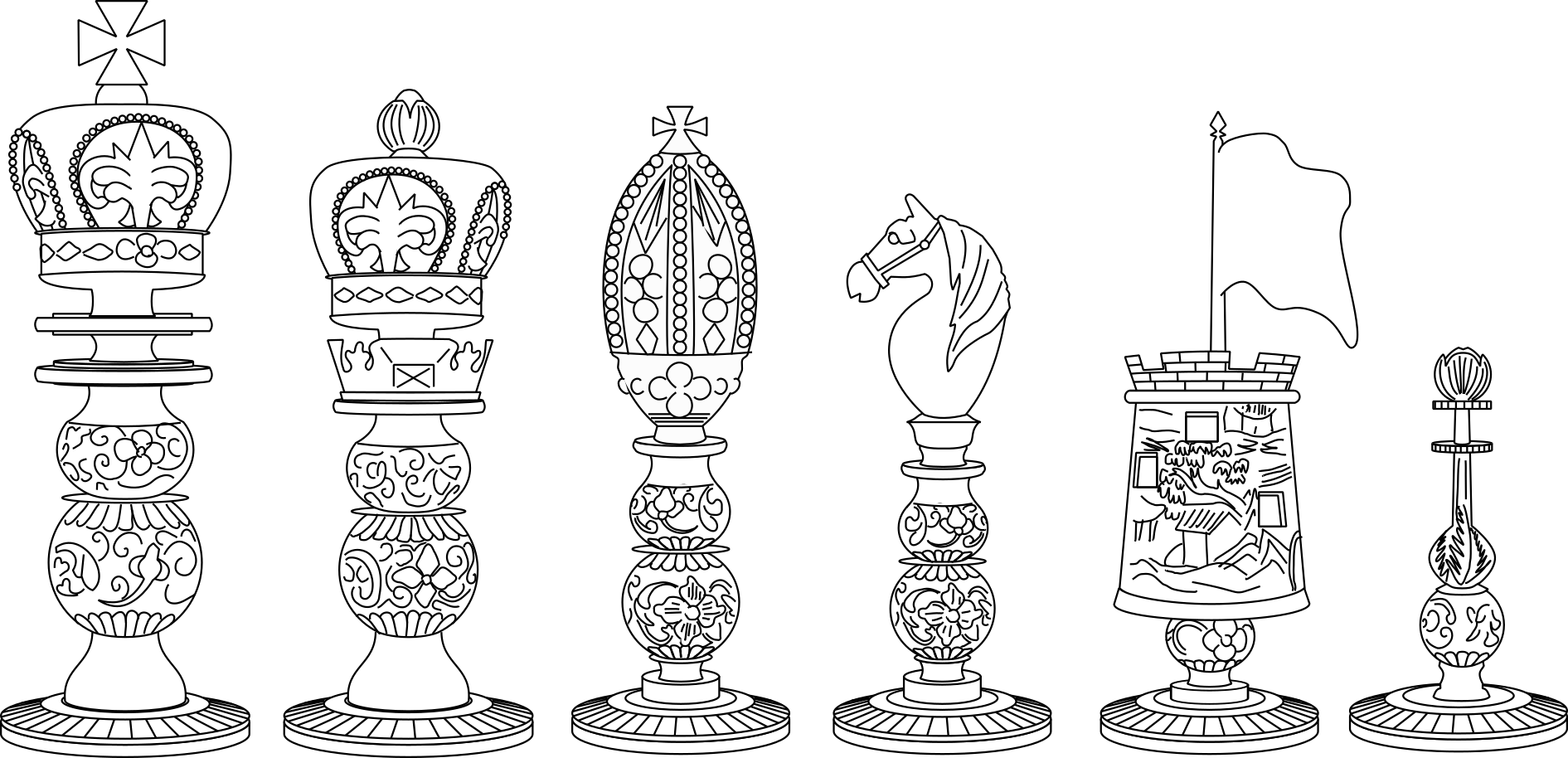

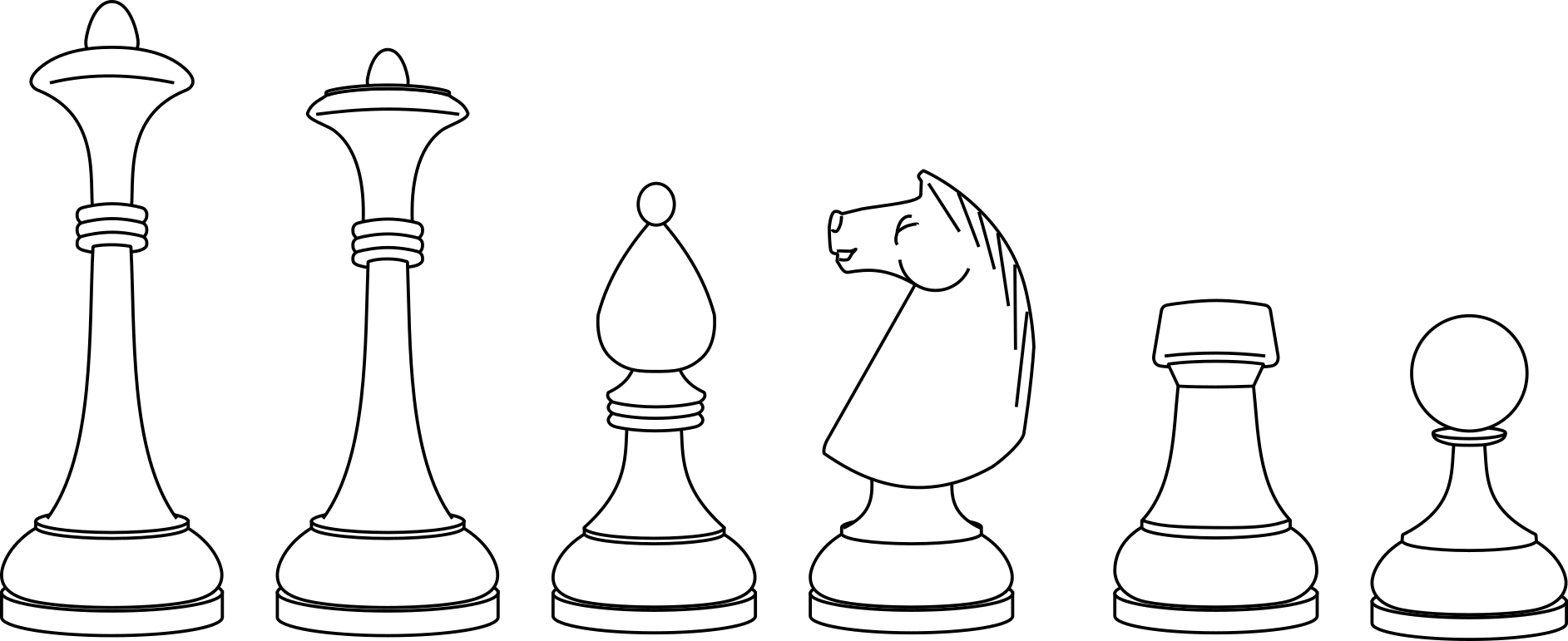

An Indian origin should be considered. They are not so far removed from Anglo-Indian export sets. Such sets, produced in several major ivory manufacturing centres in India, were made for the export market and so derived features from English designs, like horses for knights. Anglo-Indian export sets are quite varied and usually feature Kings and Queens with English-style crowns and coronets, but in other ways are quite similiar to the "Turkish" pieces. Among the various Anglo-Indian designs we see bulb shapes in stems, turrets on stems like the Cholet/Crumiller set, knights with figural heads, and floral motifs. They are also often white and green, traditional Indian chess colours, like the Cholet/Crumiller and Bronstein examples.

An English origin should also be considered. In the 19th Century there were many English imitations of the popular Anglo-Indian imports, which themselves may have been inspired by foliate English designs like Calvert's Pistil.

So, where does the Turkish claim originate from? It appears to come from Mackett-Beeson's book Chessmen, first published 1968. However (and here the plot thickens) it transpires that the set in this book was not from 19th Century Türkiye but from 20th Century Britain.

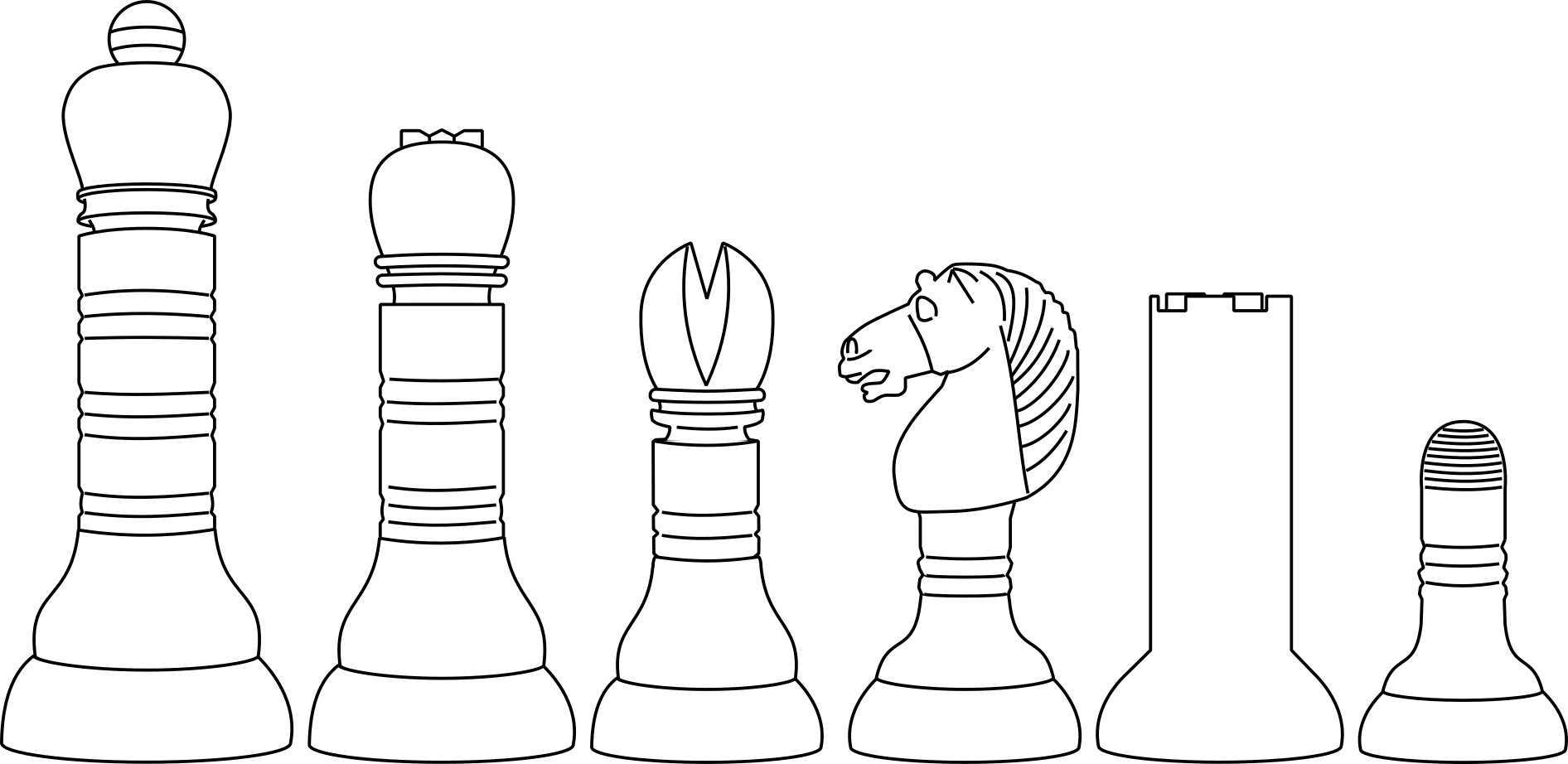

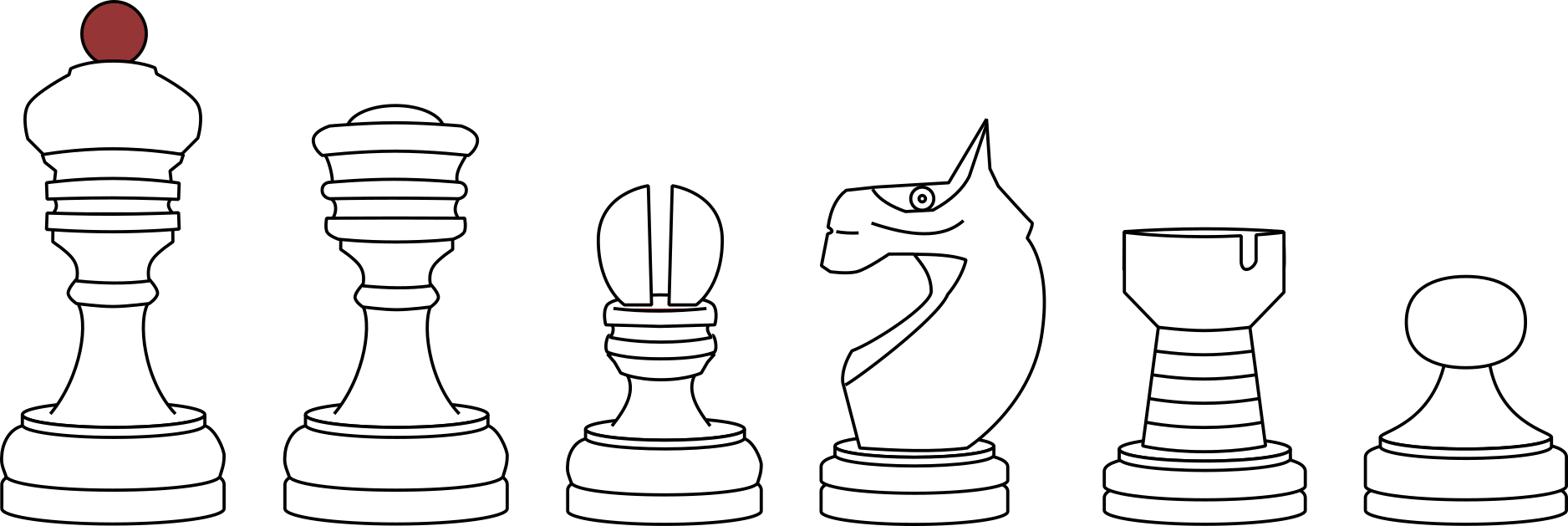

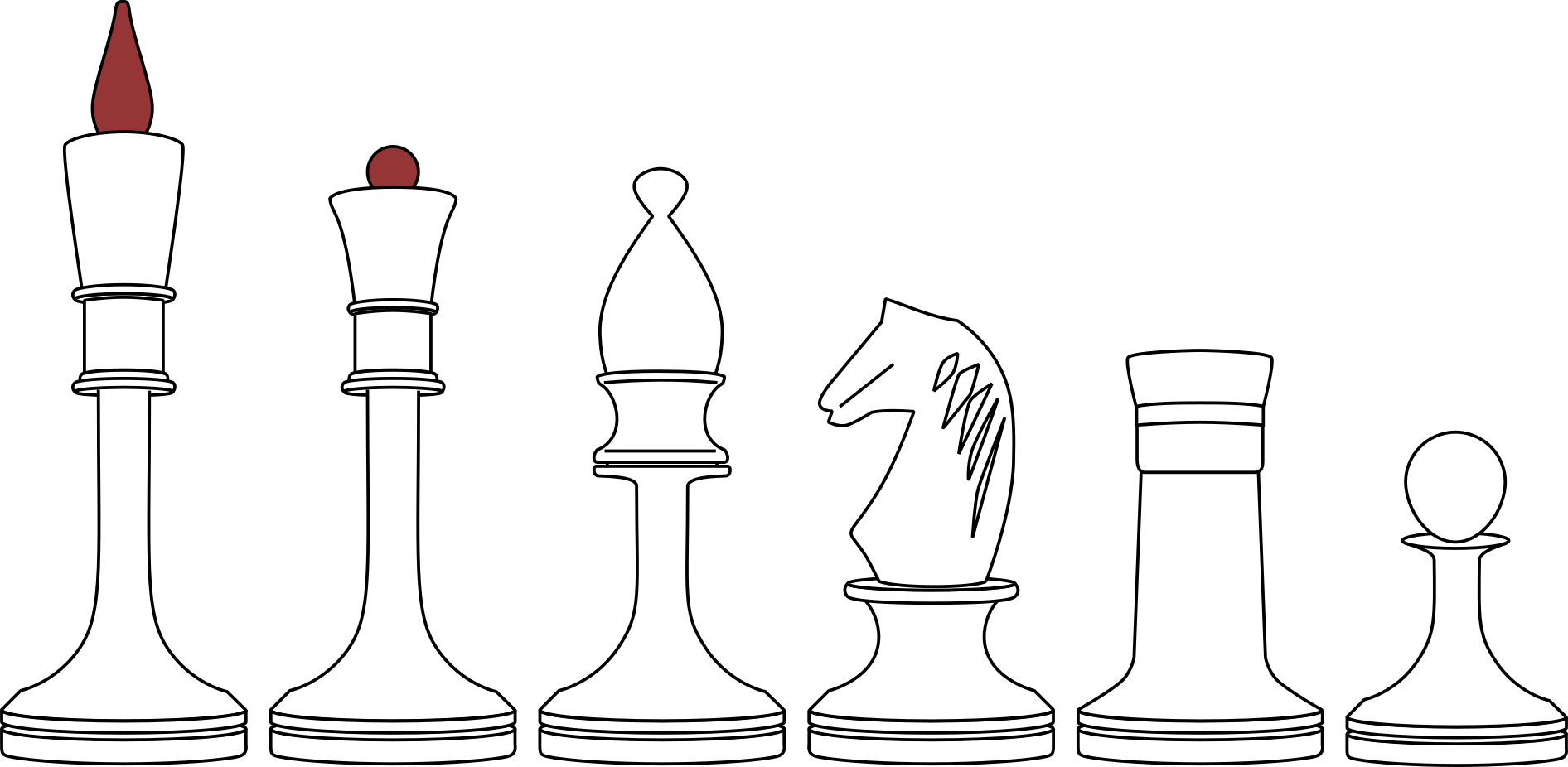

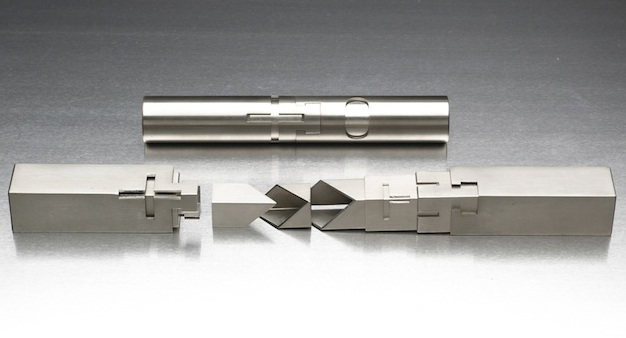

In 2006 a was sold at Christie's. It matched Crumiller's description of the "usual form" of this pattern exactly. Bertram Jones (1885-1969) was a British ivory turner and chess set manufacturer. The lot essay compares the set to the one in Mackett-Beeson's book, which was "described as Turkish and early 19th century... but now believed to be by Bertram Jones."

Now, it's very tempting to draw a line here and say "mystery solved, these sets were made by Jones in the 50s and have nothing to do with 19th century Türkiye, sorry Jon."

To his credit, Crumiller's discusses Jones in connection with his set. He writes,

several similiarly patterned sets were made by... Bertram Jones [whose speciality] was recreating different types of rare antique chess sets, using his skills, and techniques to make the sets look older than they were. Some of his sets were subsequently sold as original antiques, which was problematic at the time.

The implication being that Jones based his sets on a genuine antique, i.e. Crumiller's. This may be true but it seems hard to prove. I note that Christie's description of Jones's set doesn't claim Jones was inspired by an antique set. Rather, it repeats the rose water sprinkler legend, but now suggests it was Jones, working in the 50s, who was inspired by the sprinklers.

So it appears that the Turkish claim originated from Mackett-Beeson's book, where a Jones set was misidentified as an antique. It was then repeated in the 2007 and 2023 auctions, and Crumiller repeated it in good faith in his book. There is nothing really to support it other than the idea of chess pieces being based on water sprinklers being a quaint.

The Jones sets also calls into question the 19th Century/1900 dates, though it's possible that the auctioneers of the Cholet and Bronstein auctions had evidence other than the discredited passage in Mackett-Beeson's book to base their 19th Century date on. (I don't know if auctioneers have any tricks for dating ivory in the absense of documentary evidence anyway.)

As the only thing we known with certainty is that Jones made such pieces in the mid-20th Century, I have put them here on the timeline. Jones may have originated the design. He may, like Crumiller sugests, have based it on earlier pieces, but it is hard to be sure. If he was basing his set on older pieces, then we don't know where those pieces were from. They could as easily have been Anglo-Indian export sets as anything else.

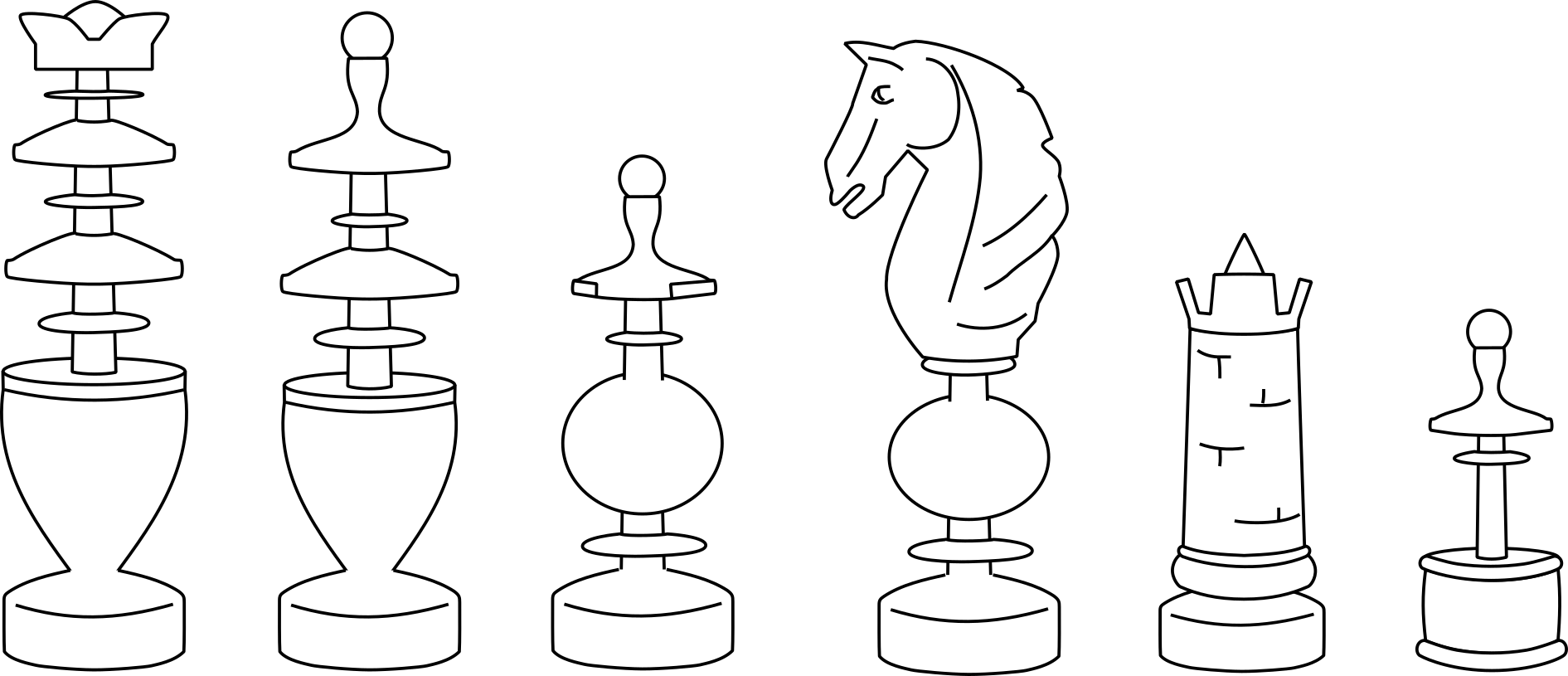

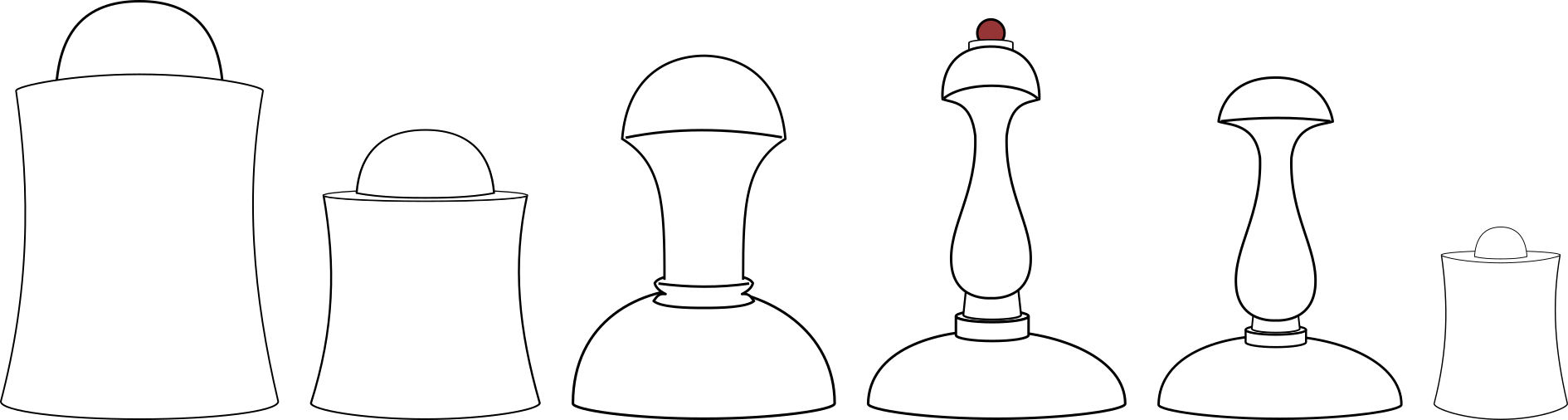

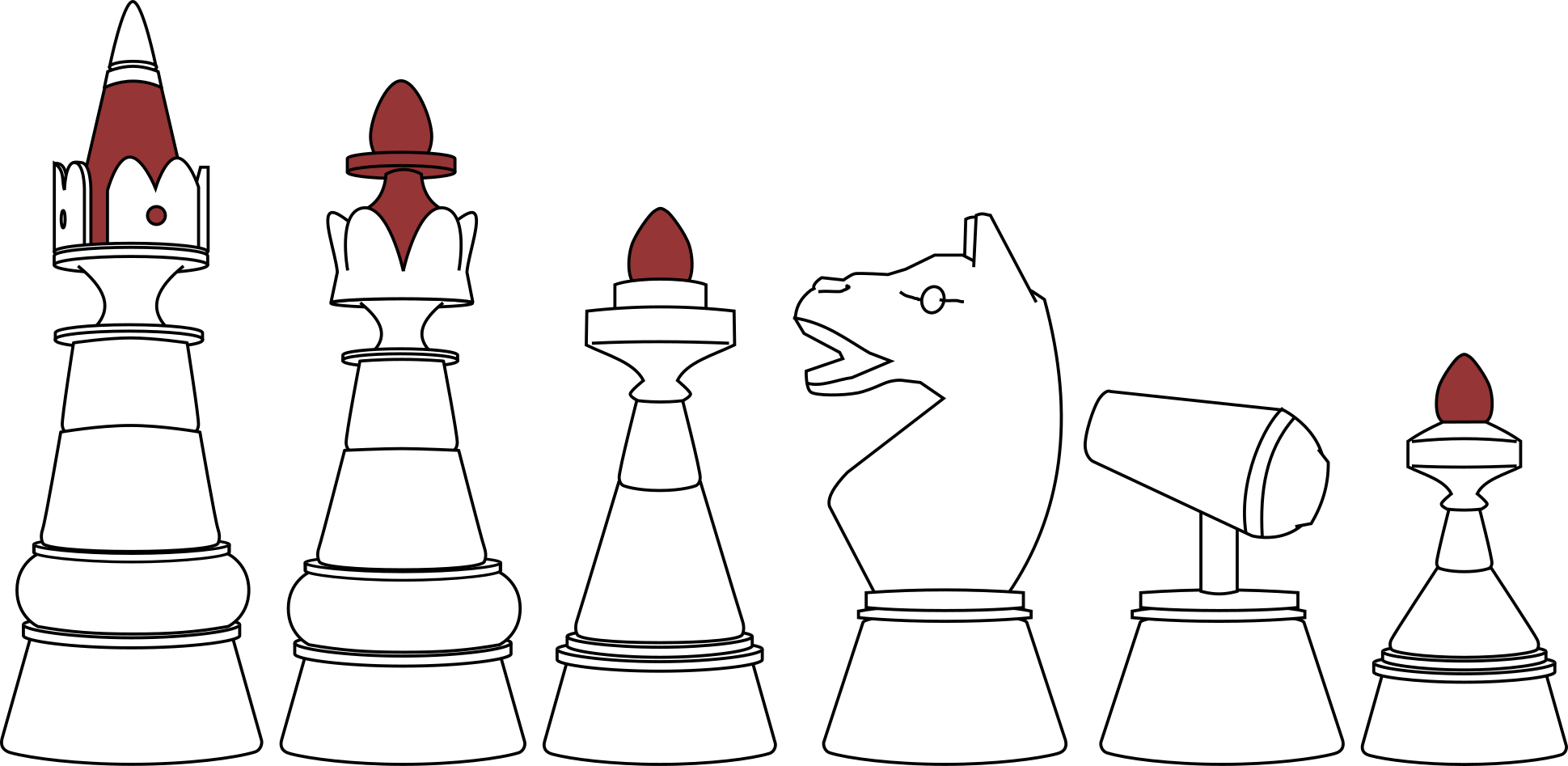

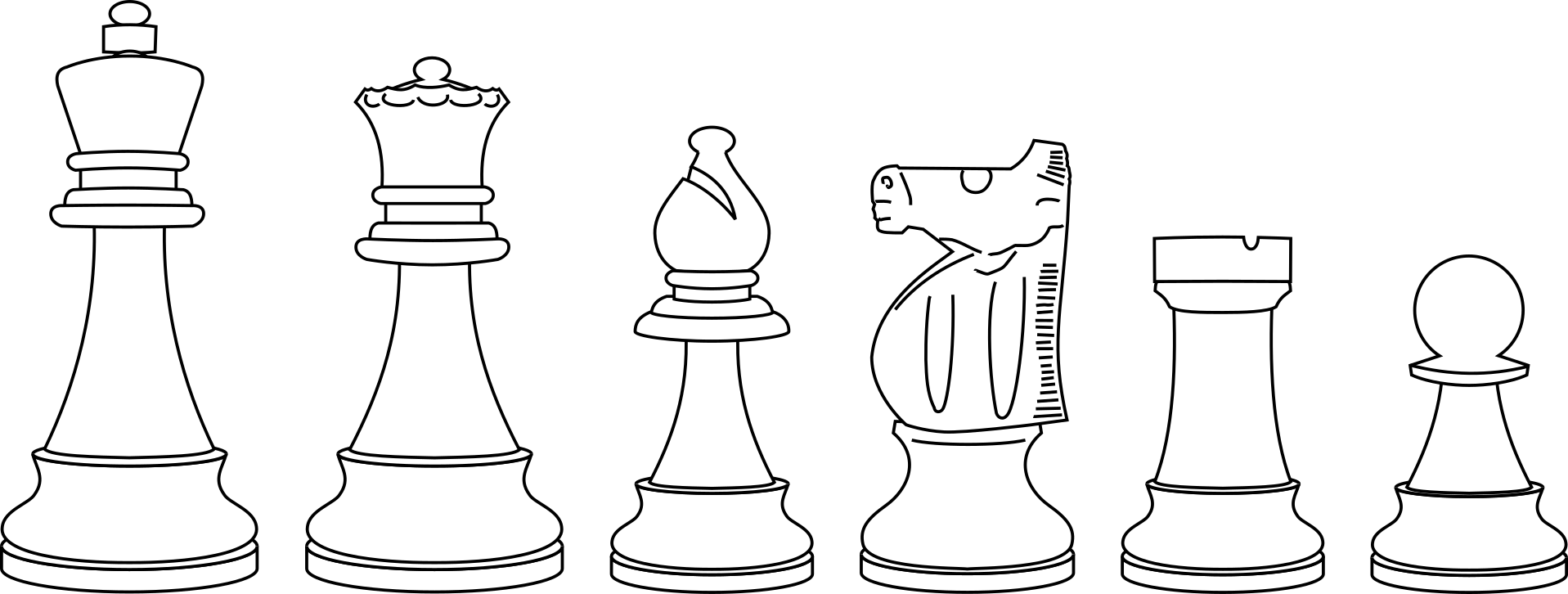

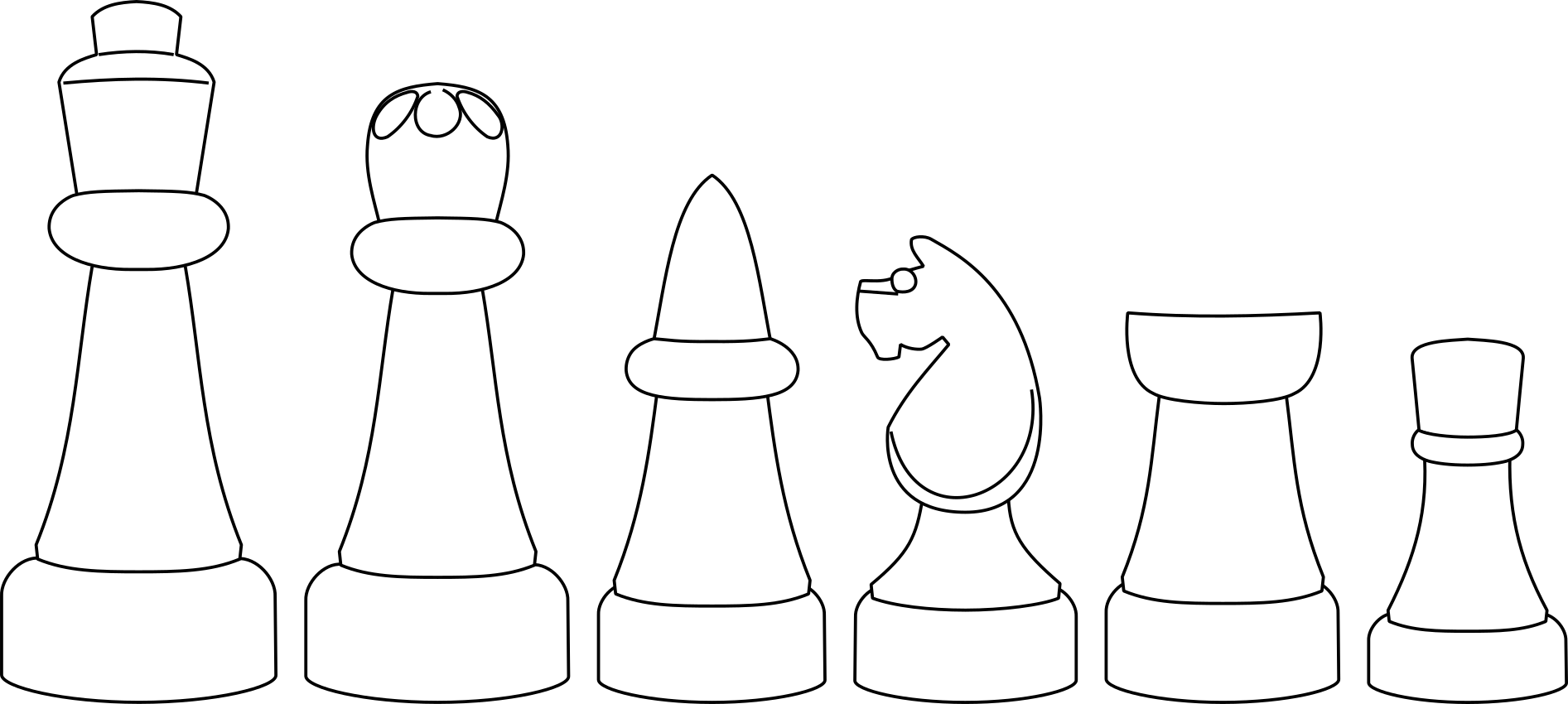

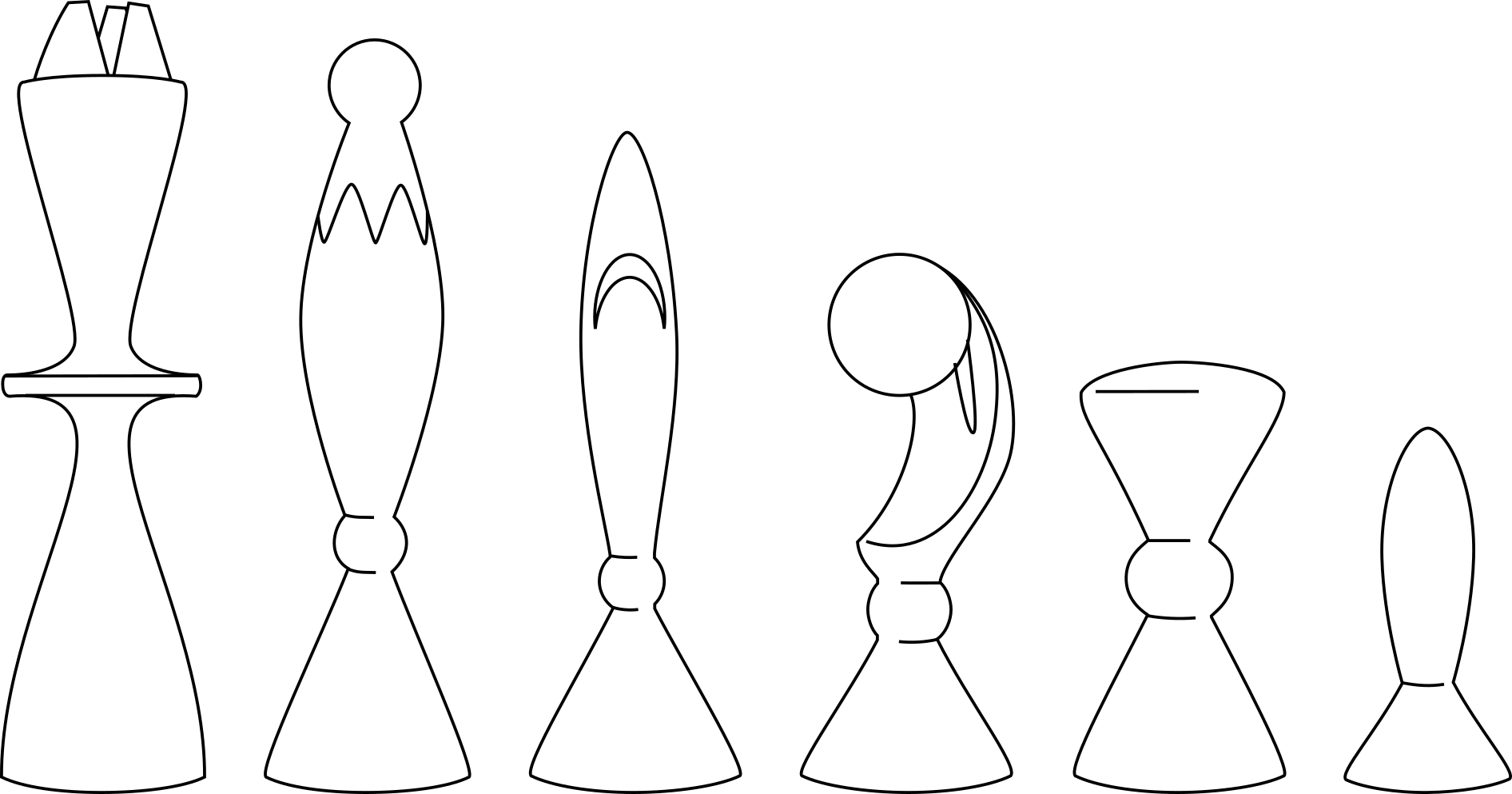

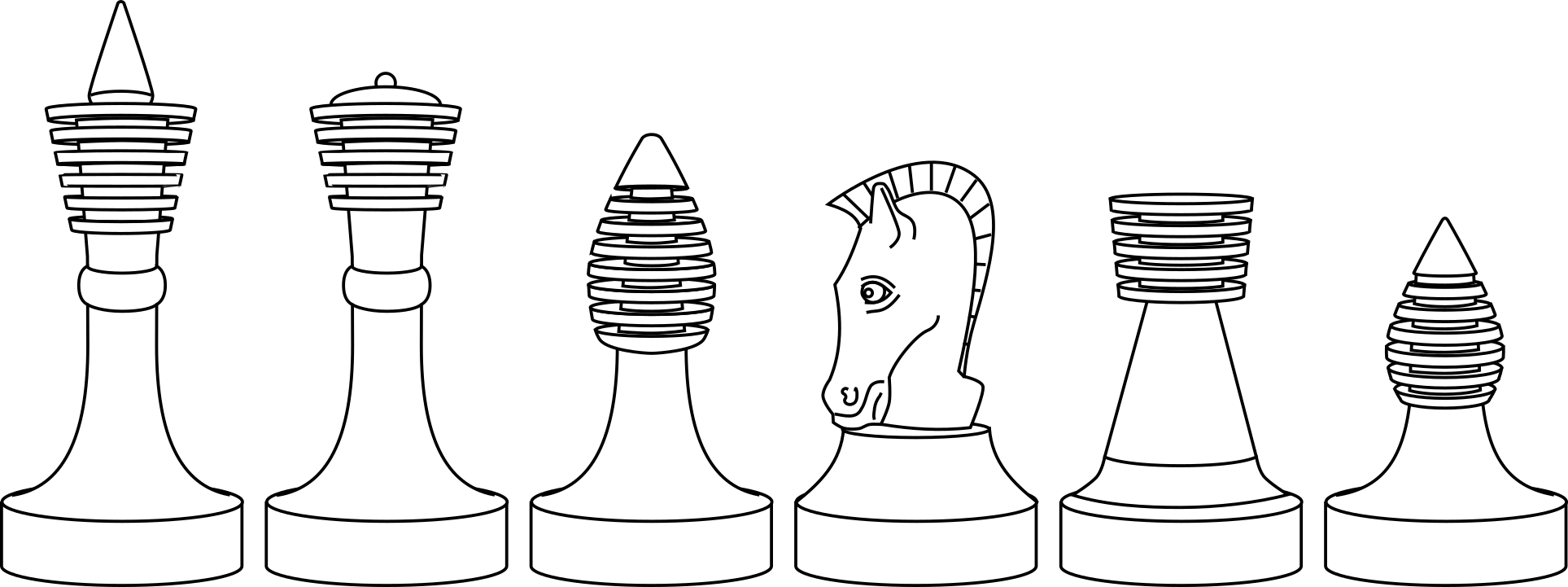

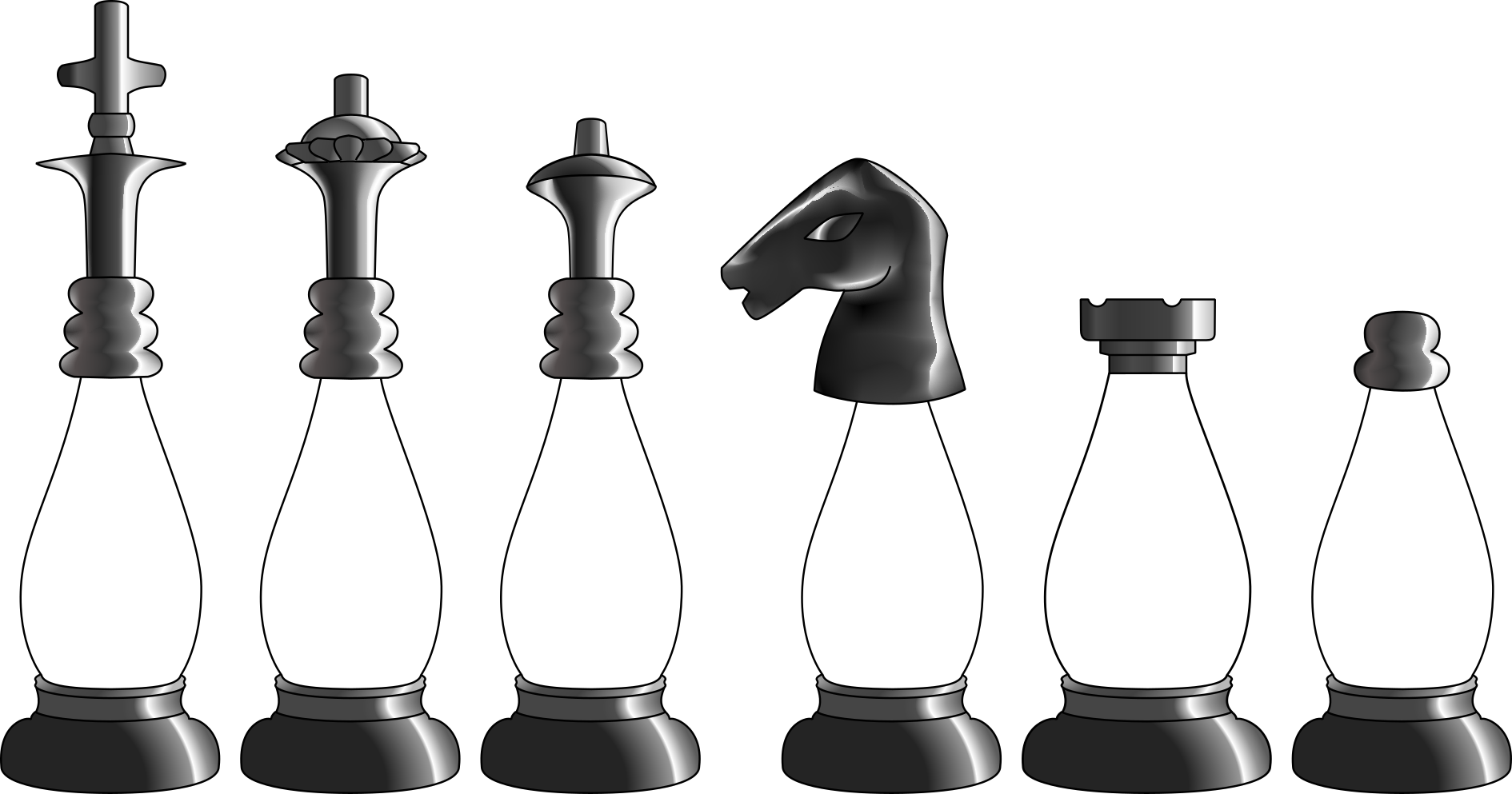

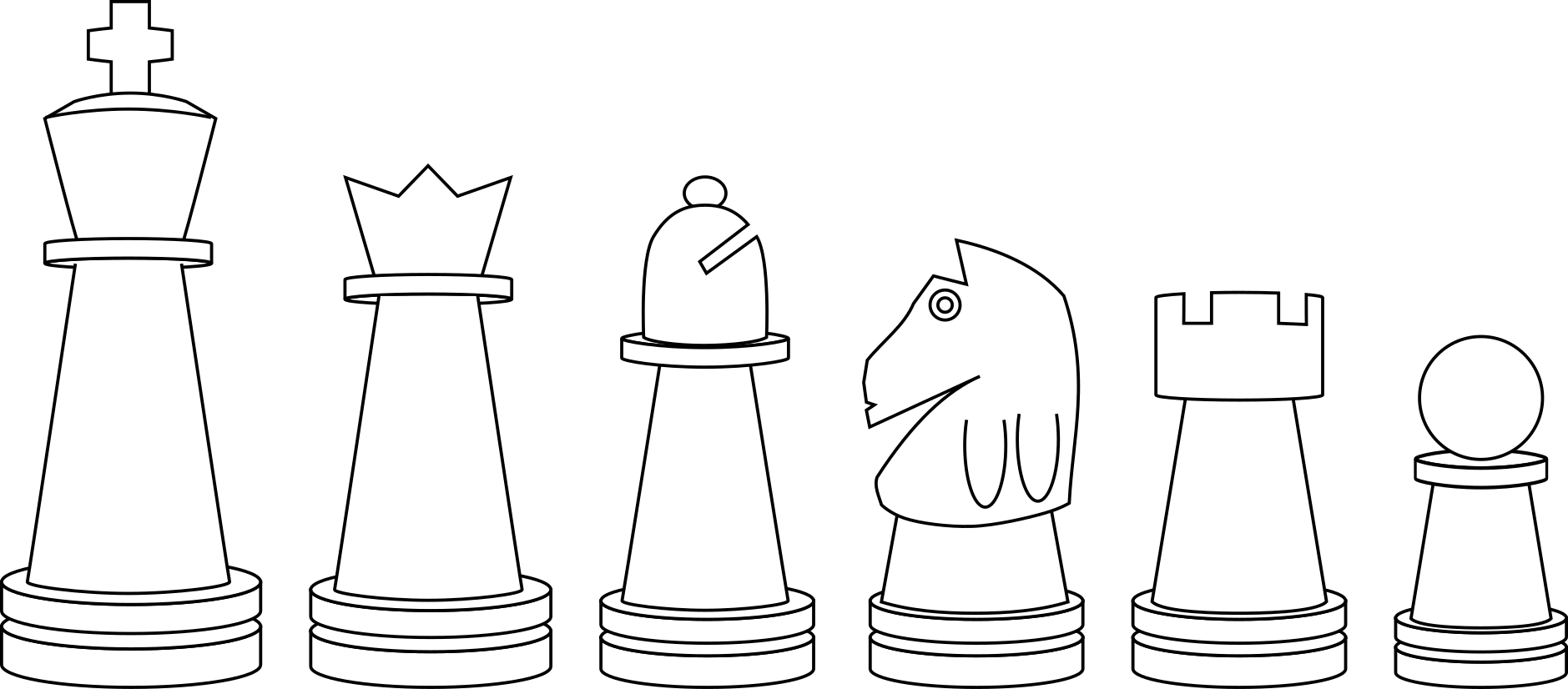

The design of Jones's set has been seized upon by Royal Chess Mail for their Turkish Tower reproduction, though not made out of ivory and far less delicate in appearance. They also call it a "Pre-Staunton" set, which even going by Crumiller's set's 1900 date it would not be.